October 26th, 1966. On the Newui Din Hills, west of the Australian Task Force Base at Nui Dat, the humidity sits at 90%. It is a physical weight pressing the sweat- soaked greens against the skin of the four men moving through the bamboo. They are Australian sass, the phantoms of the jungle.

Women’s history books

Discover more

Military documentaries

Vietnam War history

Special forces gear

SAS training programs

Camouflage clothing

Tactical knives

Women in war

Australian defense news

Military patches

Replica firearms

They do not hack through the bush. They flow through it, silent, invisible. Lead scout jock moves a branch just enough to slide his body through, then eases it back. No snap, no rustle. He halts. A hand signal ripples down the line. 10 m ahead, the jungle floor opens into a small sundappled clearing. A figure is crouching by a stream filling a canteen, black pajamas, a chom rifle leaning against a rock.

The figure turns. It is a girl no older than 19. In the milliseconds that follow, the calculus of war collides with human instinct. The rules of engagement are clear. An armed enemy is a target, but the silhouette is slight, the face young. The finger on the trigger hesitates for a fraction of a second. This is the anomaly that defined the Australian experience in Futoui.

They were trained to kill soldiers. They were not fully prepared to hunt women. The statistics were already known to intelligence officers back in Saigon. By 1966, women comprised nearly 40% of the National Liberation Front’s logistical backbone in certain districts. They were the long-haired army.

Historical fiction novels

They carried rice, they carried messages, and frequently they carried grenades. The SAS patrol is now frozen in the green twilight. If they shoot, they compromise their position. If they let her go, she reports their location to a main force battalion within the hour. Capture is the third option, the most dangerous option.

This is the story of that third option. It is not a story of mass battles or napalm strikes. It is a story of intimacy and terror. It is about what happens when elite operators trained in the dark arts of silent warfare come face to face with an enemy who looks like a school girl but possesses the resolve of a fanatic. This is the friction of capture.

Discover more

Elite soldier biographies

Combat rations

Military history books

Military themed apparel

Female soldier stories

Vietnam War history

Tactical knives

Military patches

Australian military history

Jungle boots

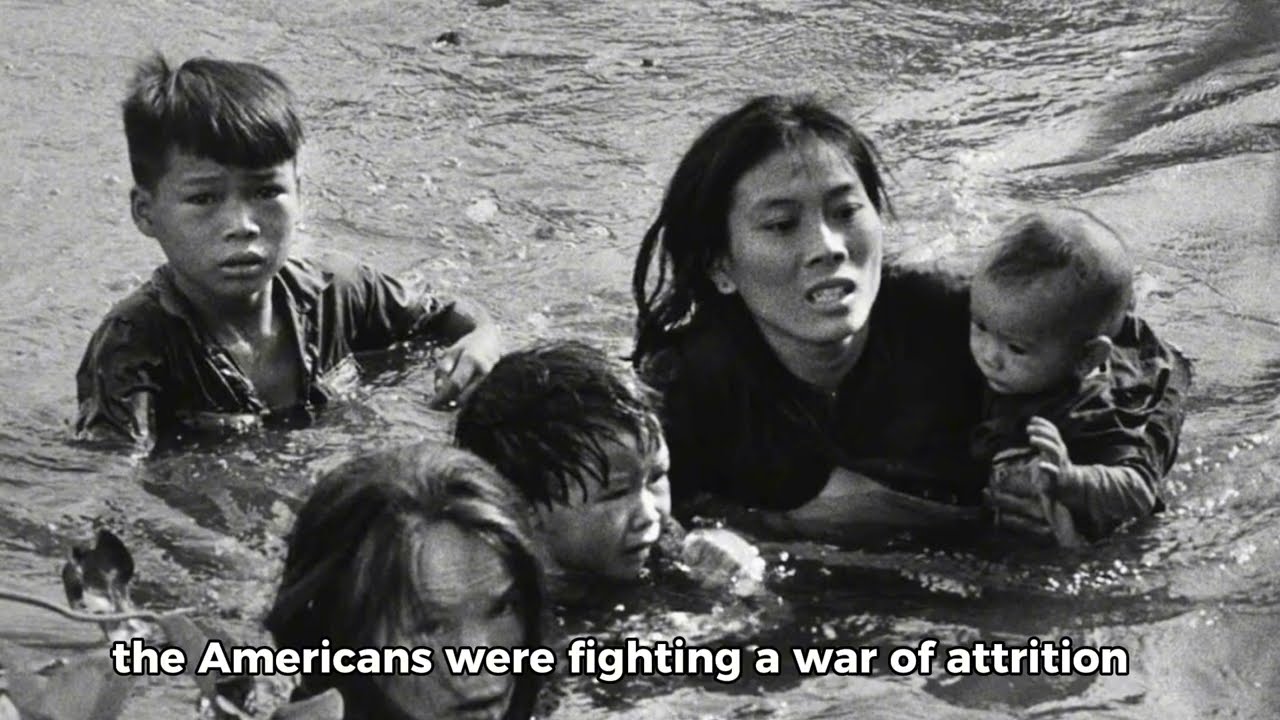

To understand the gravity of this encounter, we must first zoom out from the Newin Hills to the chaotic map of 1966. The Americans were fighting a war of attrition in the north and central highlands, a strategy of body counts and massive firepower. But down in the south, in the humid flat wetlands and jagged hills of Fui province, the Australians were fighting a different war.

Military history books

The Australian task force arrived with a doctrine forged in the jungles of Malaya. counterinsurgency. The concept was simple but exhausting. Dominate the jungle. Deny the enemy sanctuary. Patrol constantly. The tip of this spear was the Special Air Service Regiment. The SAS were not conscripts. They were volunteers, often older, more experienced.

Conflict resolution books

Many were veterans of the Malayan Emergency or Borneo. They operated in fiveman patrols, sometimes staying in the bush for weeks. Their primary weapon was not the SLR rifle, but their eyes. They were intelligence gatherers. They were ghosts. Their mission was to locate the Vietkong infrastructure, the shadow government that ran the province.

Discover more

Women in war

Conflict resolution books

Tactical knives

Military patches

SAS training programs

SAS training resources

Navigation tools

Australian military history

Military strategy guides

Elite soldier biographies

This infrastructure was not a traditional army. It was a complex biological system that lived within the civilian population. And at the heart of this system were the women. Western military tradition had drawn a hard line between combatant and non-combatant for centuries. Men fought, women and children waited.

Women’s history books

The war in Vietnam erased that line. The National Liberation Front or Vietkong viewed the struggle as total. Everyone had a role. The female cadra was organized, disciplined, and extensive. They were not just wives or camp followers. They were political officers. They were medics. They were transportation units. And they were combatants.

Intelligence reports from the era detail the specific roles. The Dan Kong were civilian laborers, often women, conscripted or volunteering to move supplies. They could carry 50 pounds of rice on their backs over jungle trails for 12 hours a day. But there were also the dedicated guerilla units, women who knew how to set booby traps, women who acted as scouts, women who could field strip an AK-47 in the dark.

For the Australian SAS, this presented a unique tactical nightmare. A patrol deep in enemy territory relies on stealth. If they are compromised, they are outnumbered 100 to one. Their survival depends on remaining unseen. When a patrol encountered a male Vietkong soldier, the decision tree was usually binary, kill or bypass.

But the encounter with a female combatant introduced a layer of hesitation that the enemy exploited. The Australian soldier of the 1960s was a product of his time. Chivalry was not dead. It was culturally ingrained. The idea of shooting a woman was abhorrent to the average digger. The NLF knew this. They weaponized it.

Military history books

There are documented accounts of female scouts walking openly on trails unarmed, acting as bait. If an Australian patrol engaged them orcaptured them, the noise and delay would draw the patrol into a preset ambush. If the patrol let them pass, the scout would simply loop back and report the Australian position. This was the environment in 1966, a chess game played in a sauna.

The SAS needed prisoners. Dead bodies provided weapons and documents, but they did not provide the current location of the D445 battalion or the secret bunker systems in the Long High Hills. Prisoners were the gold standard of intelligence. But capturing a prisoner in the jungle is one of the most difficult feats in warfare.

It requires getting within touching distance of a person who wants to kill you. It requires subduing them without firing a shot. And then it requires extracting them through kilometers of hostile terrain while they try to escape or signal their comrades. Now add the variable that the prisoner is a woman. Let us return to the patrol in the new ding hills.

The point man, usually the most alert and quick reflexed soldier in the team, signals the halt. The commander moves up. He assesses the situation. The woman at the stream is alone. This is rare. The VC almost always move in pairs or threeman cells. If she is alone, she might be a courier. Her pack could contain maps, tax collection records, letters from commanders. She is a high value target.

Historical fiction novels

The commander signals capture. The patrol splits. Two men melt into the foliage to the left, flanking the stream. Two move right. The commander and the signaler stay central, covering the approach. They move with agonizing slowness. One step, wait. Listen. One step. Wait. The woman stands up. She shoulders her rifle.

She is about to leave. The window of opportunity is closing. The flanking sass operators are within 10 m. 5 m. They can smell the charcoal from her cooking fires on her clothes. They can see the sweat on her neck. They spring. It is not like the movies. There is no dramatic music. There is just a sudden violent rush of noise in the quiet jungle.

A body tackling another body. The splash of water. The dull thud of boots on mud. The woman screams. It is a high piercing sound that cuts through the canopy. The sass soldier’s hand clamps over her mouth instantly, but the sound has already escaped. Shut up. Shut up. He hisses, though she likely understands no English. She fights.

She fights with a ferocity that shocks the Australians. She is not submitting. She is biting, scratching, kicking. She is trying to reach for the grenade on her belt. The second operator pins her arms. They drag her away from the stream into the cover of the bamboo. They are breathing hard. The adrenaline is spiking.

Conflict resolution books

Now begins the immediate terrifying protocol of the search. An Australian soldier raised in the suburbs of Sydney or the bush of Queensland is now holding down a struggling Vietnamese woman in the dirt. He has to search her. He has to check for weapons. He has to check for documents. The search must be thorough. A hidden pistol, a knife, a grenade with the pin half pulled inside a pocket.

These are death sentences for the patrol. The operator runs his hands over her black pajamas. It is invasive. It is rough. It is necessary. He finds a Chcom grenade. He tosses it to his mate who secures it. He finds a pouch with papers. He secures that. She is still struggling, eyes wide with terror and rage. She expects to be killed.

The NLF propaganda has told her that the Australians are monsters, that they eat babies, that they rape and torture. She is fighting for her life. The soldiers zip tie her wrists. They gag her, not to be cruel, but to stop the screaming that will bring a mortar barrage down on their heads. The commander checks his watch.

Two minutes have passed since the capture. That is too long. The scream was heard. They have to move. Get her up. We’re moving out. Extraction point alpha. This is the setup. The board is set. The pieces are in motion. We have an elite fiveman team deep in enemy territory, burdened with a prisoner who hates them, hunted by her comrades who are likely already closing in.

Women’s history books

But to truly understand the dynamics of what happens next, we have to look deeper into who these men and women were. The Australian SAS training focused on discipline and mental fortitude. The selection course was brutal, designed to weed out the weak and the reckless. Those who passed were calm, calculated professionals.

They were taught to observe. In the jungle, they were the alien invaders. They were big men carrying 40 kilos of gear, sweating in the heat. The female Vietkong, in contrast, were at home. This was their backyard. They were often smaller, malnourished by years of war and blockade, but hardened by a life of labor.

They knew every cave, every trail, every village. When these two forces collided, it was a clash of civilizations. The capture of a female combatant disrupted the standard operational rhythm of the SAS. With a male prisoner, the dynamic was soldier to soldier. There was a grudging respector a mutual understanding of the game. With a female prisoner, the dynamic became confused.

The soldiers became hyper aware of their actions. They were worried about accusations of mistreatment. They were awkward. The prisoner conversely often used this to her advantage. She would play the role of the innocent peasant girl. No VC. No VC. Meet me go market. She would cry. She would feain illness. She would walk slowly, dragging her feet, delaying the patrol.

And all the while she would be counting, counting the men, noting their weapons, memorizing their radio frequencies if she could hear them, watching their hand signals. She was a prisoner. Yes, but she was still a combatant. She was still at war. The intelligence gathered from these captures would prove crucial. Documents found on female couriers often revealed the tax collection networks that funded the insurgency.

Military history books

Diaries revealed the morale of the enemy units. Medical supplies revealed the sicknesses plaguing the camps. But getting that intelligence back to Nuidot required the patrol to survive the next few hours. The extraction is the most dangerous phase. The patrol is slow. They are noisy. They are vulnerable. As the team moves out, dragging the prisoner with them. The jungle feels different.

The silence is heavier. Every bird call sounds like a signal. Every shadow looks like an ambush. The pointman is working overtime, scanning for trip wires. The rear guard is walking backwards half the time, watching their trail. The two men in the middle are managing the prisoner. She stumbles. She falls.

Historical fiction novels

Is she exhausted or is she stalling? The soldier hauls her up. Come on, move. He offers her water from his canteen. She looks at it then at him. Suspicion. She thinks it might be poison. He takes a sip himself to show her. She drinks greedily. For a second, the war recedes. It is just two humans in the heat. Then she hands the canteen back and the mask returns. The eyes go hard.

They are 3 km from the extraction zone. The sun is dropping. The shadows are lengthening and then the point man stops. He raises a fist. Movement ahead. Not a single scout, a squad. The patrol has walked into a cordon. The scream was heard. The net is closing. This is the reality of the capture. It is not the end of the mission.

It is the beginning of the gauntlet. The prize they have secured. This young woman with the secrets of the district in her head has now become an anchor, weighing them down as the tide rises. The commander has a decision to make. They can fight their way through, risking the prisoner’s life and their own.

They can try to hide and wait for nightfall, or they can call for the bush rangers, the helicopter gunships. But gunships take time, and time is the one thing they do not have. The woman watches them. She sees the tension in their shoulders. She sees the hand signals. She knows her comrades are near. A small grim smile touches her lips behind the gag.

Conflict resolution books

The hunter has become the hunted. The encounter rate between Australian forces and female Vietkong was not a daily occurrence, but when it happened, it left a mark. Official records from the Australian War Memorial show numerous instances of female codgers being detained. These were not random civilians. These were active participants in the war effort.

One notable incident involved the capture of a female nurse during a bunker complex clearance. She refused to leave her patients, standing over wounded VC soldiers, even as the Australians threw grenades into the tunnel entrances. When the dust settled, she emerged, covered in dust and blood, defiant, the Australians did not shoot her. They admired her courage.

This respect was a strange undercurrent in the violence. The sass, being professionals, recognize professionalism in their enemy, regardless of gender. But respect does not save you in a firefight. Back on the trail, the patrol is shifting formation. They are moving into a defensive perimeter. The enemy squad ahead is searching.

They are sweeping the area. The SAS commander whispers into the radio handset. Contact. Contact. Wait out. He needs to coordinate an extraction, but he cannot give away his exact position yet. The prisoner starts to make a noise, a muffled rhythmic humming. She is signaling. The soldier guarding her tightens his grip.

Women’s history books

Quiet, he whispers, his face inches from hers. or you die. It is a bluff. Or is it? In the heat of the moment, with adrenaline flooding the system, the line between discipline and survival blurs. The humming stops. The soldier’s thumb presses into the pressure point behind the woman’s ear, not to injure, but to command absolute focus. The jungle holds its breath.

5 m away, a fern frond snaps back into place. The enemy search team is close enough to smell. The SAS commander makes a decision that defines the regiment’s doctrine. Evade. Firepower is a failure of stealth. He signals ghost walk. The patrol moves. They do not walk. They flow. They lift their boots high toclear the undergrowth.

Placing the outer edge of the sole down first, rolling to the instep. Silence is not an absence of noise. It is a discipline. But the woman high does not know the ghost walk. She is a peasant, a gorilla accustomed to the swift crouching run of the Vietkong, not this agonizingly slow ballet. She drags her feet. She stumbles intentionally. She is a weapon now.

Her body a beacon trying to alert the squad hunting them. The rear gunner grabs her shoulder, stabilizing her. He does not strike her. Violence creates noise. Noise brings death. Instead, he whispers a single word in fractured Vietnamese. D go. They move 10 meters in 5 minutes, then 20.

Historical fiction novels

The voices of the VC search party drift to the left, then fade into the chaotic green wall behind them. They have ghosted the cordon, but the danger shifts from tactical to physiological. The extraction point is a rocky outcrop on the spine of the Newins 2 km uphill. The heat is a solid wall. A soldier carries 40 kg of kit, ammunition, radio, water, rations.

Now they must also manage a prisoner who is dead weight. This is where the romanticism of the guerilla war dissolves into the brutal mathematics of caloric expenditure. The prisoner high is likely malnourished. Intelligence reports from 1966 indicate that the average NLF fighter in Futoui was operating on less than 1,800 calories a day, primarily rice and tapioca.

She is small, perhaps 45 kg, but a resisting 45 kg is heavier than 100 kg of dead weight. She collapses. It is not an act. Her legs, fueled by adrenaline during the capture, have turned to water. The patrol halts. The commander looks at the sun. 1630 hours. The shadows are stretching, turning the jungle floor into a mosaic of black and gray.

If they don’t make the LZID landing zone by 1700, the choppers won’t come. The RF Royal Australian Air Force pilots are brave, but night extractions in Indian country are a violation of standard operating procedures unless the team is in immediate danger of being overrun. Carry her, the commander orders. It is an absurdity of war. A hulking sass trooper painted in camouflage cream slings his weapon and hoists the enemy combatant onto his shoulder like a sack of rice.

Conflict resolution books

He smells of cordite and stale sweat. She smells of woodsm smoke and fear. For the next kilometer, they are physically joined. The hunter carrying the prey to safety. During this ascent, we must pause to look at the enemy they are carrying. Who is she? Statistically, she is likely a local girl from the Datau or Long Deian districts.

The Australian intelligence analysis of 1967 estimated that in some villages up to 80% of the youth were affiliated with the NLF. She did not necessarily join because of Marx or Lenin. She joined because her brother was killed by an artillery shell. She joined because the government in Saigon felt like a foreign occupation.

She joined because in her world, the Vietkong were the government. She is part of a system the Australians called the VCI, Vietkong infrastructure. It was a shadow state. They collected taxes, ran schools, and administered justice. And the women were the glue. A captured document from the Chow Duck District noted, “The sisters are the eyes and ears of the revolution.

They are the water in which the fish swim, but right now the fish is out of the water. They breach the tree line. The LZ is a patch of elephant grass flattened by the wind.” The radio operator, the Sig, keys the handset. Albatross, this is one zero at the extraction point. One pax hot.

Women’s history books

Pax is the sanitized military term for a passenger or prisoner. Hot implies the potential for enemy fire. The response is immediate. The distant thrum of rotors, the sound of the Vietnam War. It starts as a vibration in the chest and grows into a mechanical shriek. Two UH1 Irakcoy helicopters appear over the ridge. Gunships, the bush rangers.

They bank hard, their door gunners scanning the treeine. M60 machine guns hanging on bungee cords. The downwash hits the patrol like a physical blow. Dust, grass, and debris swirl in a violent vortex. For High, this is the moment of peak terror. She has seen these machines from the ground, firing rockets and miniguns. She has never been under one.

The noise is deafening, a sensory overload that shatters the mind. She curls into a ball. The SAS trooper drags her toward the open door of the hovering chopper. The skid touches the rock. The door gunner beckons, his face hidden behind a visor and helmet. To her, he looks like an insect, a demon. They throw her in. The SAS team piles in after her.

The engine screams, the pitch changes, and the earth falls away. This is the psychological break for a Vietkong fighter. Their power comes from the land. They know the tunnels, the trails, the caves. The moment the skids leave the ground, she is severed from her source of strength. She is suspended in the sky in the belly of the beast.

She looks out the open door. The jungle. Herjungle is just a green carpet below. She sees the bomb craters, the brown scars of defoliant, the red lerite roads. It is a view of her country she has never seen. It makes her feel small. The sass men relax instantly. The transition is jarring.

Historical fiction novels

A moment ago, they were apex predators, tense and lethal. Now they light cigarettes. The wind whips the smoke out the door. They check their weapons. One offers her a stick of chewing gum. She stares at it. She doesn’t know what it is. Is it a drug? A poison? The soldier unwraps it and chews a piece himself. Smiling with his eyes. He puts a piece in her hand.

She clutches it but does not eat it. The flight is short, 15 minutes. They cross the new dins and descend towards the Australian task force base at Nuidat. If the jungle was the domain of the guerilla, Nuidat is the fortress of the occupier. From the air, it is a shock of geometric order imposed on the chaos of nature.

Rows of tents, sandbag walls, artillery pits, vehicle parks. The red dust of Fuktui coats everything. The chopper flares, the nose pitching up to bleed speed and settles onto the perforated steel planking of Luskome Field. The engine winds down. The handover begins. The SAS patrols job is done. They are the hunters. They do not skin the game.

Two MPs, military police, are waiting. They are clean, their uniforms starched compared to the jungle rotted greens of the SAS. They take high by the arms. She is led away from the chopper, her legs wobbly on the steel matting. She looks back at the SAS team. They are already walking away towards their trucks, talking about beer and showers. They have forgotten her.

Conflict resolution books

She is taken to the intelligence section. The cage. This is a series of tents and bunkers surrounded by razor wire. It is the processing center for all detainees. Here the war changes from a physical struggle to a mental one. The processing of a female prisoner was a delicate matter for the Australian army. The Geneva Convention was strictly adhered to on paper, but the reality of interrogation is always a gray zone.

First, the search. A female nurse or a female interpreter is usually brought in if available. If not, it is done by male staff, creating an atmosphere of humiliation and intense vulnerability. Her black pajamas are searched again. The seams are checked for suicide pills or microfilm. She is given a number.

Her name is recorded, but for the system, she is now a file. Then the medical check, an Australian doctor, an RMO, regimenal medical officer, examines her. This is often the most disorienting part for the prisoner. She expects torture. Instead, she gets a stethoscope. The doctor checks for malaria, for worms, for shrapnel wounds.

He cleans the leech bites on her ankles. He gives her antibiotics. This is scops, psychological operations in its purest form. The narrative of the NLF cadres is that the Australians are barbarians. When the barbarian treats your infection and gives you a clean bandage, the ideological foundation begins to crack. But kindness is just the opening move.

The interrogation room waits. It is a tent, hot and stifling, a table, three chairs, a bright light, though it is day. The interrogator is usually a captain or a warrant officer from the Australian Intelligence Corps. Beside him sits the interpreter, often a South Vietnamese soldier attached to the task force. This dynamic is crucial.

Women’s history books

The prisoner fears the South Vietnamese interpreter far more than the Australian officer. To the ARVN, Army of the Republic of Vietnam, she is a traitor. The civil war between North and South is personal, bloody, and filled with hate. The Australians are just foreigners passing through. The interrogation begins not with shouting, but with silence. The captain lights a cigarette.

He offers one to high. Tenagi, what is your name? She stays silent. The name rank serial number. Rule is for regular armies. Gorillas have no serial numbers. They have cover stories. I am a rice farmer, she says, her voice trembling but defiant. I was looking for my buffalo. The captain nods. He has heard this a thousand times.

Every VC captured in Fuktui is looking for a lost buffalo. He opens a folder. He places a photograph on the table. It is not a photo of her. It is a photo of the unit she was with or a photo of a village chief who was assassinated last week. We know you are not a farmer. Hi, the interpreter translates. We know you are with the D445 battalion logistical group.

We know you move supplies from Shuenmach to the Long Heis. The shock on her face is microscopic, but the captain sees it. The intelligence network is working. The Australians have their own eyes and ears. This is the development phase of the script where we move from the kinetic action of the jungle to the systemic machinery of the war.

We see that the capture was just the tip of the spear. The shaft of the spear is a massive intelligence apparatus designed to map the human terrain of the province. Between 1966 and 1971, theAustralian task force screened thousands of civilians. They developed a census of the population. They knew who was related to whom.

They knew which families had sons in the north and which had sons in the ARVN. For a female prisoner like Hi, the pressure is different than for a man. The interrogators play on family. Your mother lives in Hoalong village. Yes, we can make sure she gets extra rice. Or we can let the local police know that her daughter is VC.

The threat of the white mice. The South Vietnamese police is the hammer. The Australians are the velvet glove. Hi sits in the chair. She is exhausted. She is clean for the first time in months. Her stomach is full of Australian ration packed stew. And she is terrified. She has to make a choice. Hold out and be handed over to the South Vietnamese authorities at the provincial prison in Baharia, where the stories of tiger cages and electric shocks are legendary, or talk to this calm Australian man with the blue eyes.

Give him a cash location, a name, a trail, and maybe, just maybe, go home. But the story of the female Vietkong is not just about victimhood. It is about agency. Many of these women were harder than the men. There is a recorded account of a female codger captured near the horseshoe outpost.

During interrogation, she lunged for the interpreter’s pistol. She didn’t want to escape. She wanted to kill one more enemy before she died. Another account details a woman who gave false coordinates for a weapons cache. She led a patrol into a booby trapped zone. She walked at the front smiling and took the blast of the mine herself just to take three Australians with her.

Historical fiction novels

The sass learned this the hard way. A prisoner is never truly safe until they are behind wire. And even then, their mind is still fighting. As night falls over new, high is placed in a holding pen. It is a sandbagged pit with a canvas roof, a cot, a bucket. A guard stands outside slapping mosquitoes. She lies down.

She listens to the sounds of the base, the distant thud of artillery, the 105mm howitzers firing, harassment and interdiction. Missions into the jungle. She just left. She imagines her comrades in the bunkers listening to the same explosions. She is alone in a city of men, 4,000 Australian soldiers. The gender imbalance amplifies the isolation.

She is a curiosity, an anomaly, a threat, and a prize. In the officer’s mess, the SAS commander is debriefing. He traces a line on the map. She was here alone, waiting. The intelligence officer marks the spot with a red grease pencil. That’s a courier route. If she talks, we can interdict the supply line for the upcoming dry season offensive.

She’s a tough little thing, the sass man says, nursing a beer. Didn’t make a sound when we grabbed her. Bit the hell out of Miller, though. They laugh. It is a nervous laugh. The laughter of men who survive by turning horror into an anecdote. But back in the cage, Hi is not laughing. She is weeping silently. Not for herself, but because she failed.

Women’s history books

She did not deliver the message. She did not detonate the grenade. She is alive. And in the code of the revolution, survival in captivity is a complicated shame. Day three. Inside the tent, the air is stagnant, heavy with cigarette smoke and the smell of wet canvas. The psychological architecture of the interrogation has shifted.

The initial shock of capture has worn off, replaced by a grinding fatigue. Hi has not slept for more than two hours at a stretch. The management of her sleep is deliberate. Just as she drifts off, a guard rattles the wire or the lights change or she is moved to a different chair. It is not physical torture. The Australians are strict about that, but it is a dismantling of the ego.

The intelligence officer, Captain Vance, plays the long game. He knows that ideological fervor burns hot, but burns out fast when fueled by hunger and isolation. He places a bowl of hot rice and fish sauce on the table. It smells like home. It smells like her mother’s kitchen in Long Diane. We don’t want to hurt you. Hi, Vance says softly.

But major tongue here. He gestures to the South Vietnamese interpreter, a man with hard eyes and a scar running down his jaw. Major tongue thinks you are waste. He wants to send you to Kansan Island. Do you know Consan? High flinches. Everyone knows Kansan. The tiger cages, the lime pits. It is a place where people go to turn into ghosts.

This is the lever, the fear of their own countrymen. The Australians position themselves as the protectors, the buffer between the prisoner and the real war. I can keep you here, Vance continues. I can get you a job in the messaul. I can get a message to your family, but you have to give me something. Not everything, just something, she looks at the rice, then at the interpreter, then advance.

Conflict resolution books

The calculus of loyalty is colliding with the instinct for self-preservation. The cave, she whispers. The interpreter leans in aggressive. What cave? The hospital, shesays. In the Maya Mountains near the waterfall. Vance pulls the map. Grid reference. She hesitates, then points a trembling finger at a cluster of contour lines. There beneath the rock shelf.

They have they have many wounded. The mood in the room snaps from persuasion to operation. Coordinates are verified. Frequencies are cleared. The Australian war machine which had been idling roars into gear. This moment represents the turning insight. The female combatant is no longer a generic enemy.

She has just become a human asset and she has just betrayed her comrades. Why did she do it? Was it the rice, the fear of prison? Or was it the hope that by revealing the hospital, the Australians with their doctors and medicine might treat the wounded better than the starving VC medics could? It is a paradox of the heart that no manual can explain.

Cut to the reaction force, Sixth Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. The intel is hot. An air mobile assault is planned immediately. The SAS provided the key, but the pigs, the infantry, will kick down the door. We cut to the LZ. Soldiers loading into Hueies. They are told they are hitting a fortified bunker system. They are locked and loaded.

They expect resistance. They expect a fight. The helicopters swarm over the Mtown Mountains. The terrain is brutal. Steep jungle-covered slopes that look like a green ocean frozen in a storm. The Hueies hover above the canopy. Soldiers repelling down ropes because the trees are too dense to land.

They move toward the coordinates high provided. The silence is eerie. No birds, no monkeys, just the crunch of boots and the heavy breathing of men. They find the entrance. It is camouflaged so perfectly that you could walk past it at 2 m and see nothing. A soldier pulls back a screen of vines. A dark mouth in the rock. Frag out.

A digger yells, prepping a grenade. Hold fire, the lieutenant screams. Listen. From inside the cave, there is no gunfire. There is moaning. The smell hits them first. It is the smell of gang green, old blood, and unwashed bodies. It is the smell of misery. The Australians enter with flashlights taped to their rifles. The beams cut through the gloom.

It is not a fortress. It is a charal house. Lying on bamboo mats are 30 men and women. Some are missing limbs. Some are shaking with malaria. They look at the giant Australians with eyes that have gone beyond fear into apathy. But here is the detail that inverts the scene. Here is the shock that reframes the entire narrative of the war for the soldiers standing in that cave.

Women’s history books

The lieutenant shines his light on a stack of medical crates in the corner. He steps closer. He wipes the dust off the label. Department of Supply, Commonwealth of Australia. Penicellin, morphine, bandages. The supplies in the Vietkong Hospital are Australian. The revelation hits like a physical blow. These drugs were likely stolen from the docks in Vongtao, sold on the black market in Bahra, bought by VC agents, likely women like Hi, and carried up these mountains on human backs to treat the very soldiers trying to kill the Australians.

It is a closed loop of irony. The Australians are funding their own enemy’s survival. Back in Nuidot, Hi sits in her cell. She does not know what is happening in the cave. She only knows she has crossed a line she can never uncross. The soldiers in the cave begin the work. It is not the work of killing. It is the work of processing.

They become orderlys. They carry the enemy wounded out into the light. They give water to men who hours ago would have shot them. This is the complexity of the Australian war. It was intimate. In the American sector, this might have been an air strike. In the Australian sector, it was a face-to-face encounter with the consequences of violence.

One of the wounded is a woman. She is the head nurse. She glares at the Australians as they bandage her leg. She spits at the medic. Why? The medic asks, wiping the spit away. We’re helping you. She doesn’t speak English, but her eyes say it clearly. You are the disease. The bandage does not cure the invasion. The raid yields intelligence that ripples through the task force.

Conflict resolution books

Documents found in the cave reveal the entire logistical structure of the D445 battalion. Names, safe houses, drop points. Because of High’s betrayal, the network begins to unravel. In the days that follow, the Sassin MPs launch a series of cordon and search operations in the villages of dodo and Haong.

They don’t kick down doors at random anymore. They have a list. They walk into a house. They find a woman cooking rice. They check her ID card against the list Hi provided. It matches. She is arrested. She’s the sister of the local guerilla chief. She’s the one who buys the penicellin. The system is working. The dominoes are falling. But let us return to high.

The climax of her story is not a battle. It is a conversation. Captain Vance enters the tent one last time. He places a piece of paper on the table. We checkedthe cave, he says. We found them. Hi, looks up. My brother, she asks, “Was he there?” Vance pauses. This is the moment where the omnisient narrator zooms in to the microscopic level of human cost.

There was a young man, Vance says. Leg wound, gang green. He didn’t make it. He died before the dust off chopper arrived. Hi does not scream. She does not cry. She simply folds in on herself. The gamble failed. She betrayed her cause to save her blood and the war took both. This is the thesis confirmation. The capture of female Vietkong did not just yield data.

Historical fiction novels

It revealed the tragic interconnectedness of the conflict. The enemy was not a nameless horde. It was a family. And the Australian soldier, despite his training, his technology, and his discipline, could not sever those bonds without destroying the human beings holding them. The intelligence gained from high saves dozens of Australian lives in the next month. The supply lines are cut.

The ambushes stop for a while. The sass are congratulated, but the victory is hollow. As the sun sets over Newotent to the girl in the cage, she is no longer a combatant. She is no longer a threat. She is just a casualty who is still breathing. The end of High’s utility to the Australian task force marks the beginning of her true descent.

It is a Tuesday morning. The dry season heat is building a shimmering haze over the runway at Nuidat. A convoy of trucks is idling at the main gate. These are not Australian trucks. They are Americanbuilt two-tonon trucks painted with the markings of the Republic of Vietnam National Police. The white mice. Captain Vance stands by the holding pen.

The paperwork is signed. The exploitation phase is complete. Hi has given up the hospital, two dead drops, and the names of three local suppliers. In the cold arithmetic of intelligence, she has been squeezed dry. The SAS commander who captured her watches from a distance. He is cleaning his rifle. The rhythmic snick clack of the bolt mechanism acting as a metronome.

Women’s history books

He does not wave goodbye. There is no sentimentality here, only a grim recognition of the conveyor belt. The Australians catch them. The Americans bomb them. The South Vietnamese imprison them. Two policemen get out of the truck. They wear pristine white uniforms and sunglasses. They look like traffic cops.

But their reputation in Fuktui is darker than the jungle at midnight. They take custody of High. They do not treat her with the distant clinical curiosity of the Australians. They treat her with contempt. To them, she is a traitor to the nation, a communist atheist, a disease. They shove her into the back of the truck.

She stumbles, her hands zip tied behind her back. She looks out through the slats of the truck bed. She sees the Australian flag flapping lazily over the base. She sees the young soldiers playing cricket on a dusty pitch near the tents. It is a surreal tableau of suburban normaly imposed on a war zone. Then the engine roars and the truck lurches forward.

She is leaving the sanctuary of the foreign occupier and returning to the jurisdiction of her own people. Destiny Kansan. The destination for high value or hardened female cadras was often the Kansson Island prison complex situated off the coast. It was the Devil’s Island of Vietnam. For a girl from the rice patties of DDo, the journey to Kanson was a journey to another planet.

Conflict resolution books

She is loaded onto a boat or a plane, stripped of her identity, and thrown into a system designed to break the human spirit. Historical records indicate that the treatment of female political prisoners was particularly brutal. The tiger cages, small stone pits with iron grates for ceilings, became infamous. Prisoners were shackled to the floor.

Lime was thrown down on them when they asked for water. But here is the twist. Here is the failure of the strategy. Prisons like Kansson did not break the Vietkong. They hardened them. They became universities of revolution. Inside the cells, the women organized. They taught each other to read and write.

They held political education classes in whispers. The older coders, the veterans of the French War, mentored the younger ones like high. They can chain your body. An elder sister would whisper through the stone wall, but they cannot chain your mind. Every day you survive is a victory. Hi, who entered the prison as a terrified girl who had betrayed her unit to save herself, would leave it years later as something else entirely.

The shame of her betrayal would be cauterized by the suffering. She would be reborn not as a victim but as a martyr in waiting. Back in Faultoui, the war ground on the year turns to 1968. The Ted offensive. The illusion of control shatters. The very villages the Australians thought they had pacified erupt. The Sass continue their work.

They are the masters of the jungle. Their kill ratios are astronomical, sometimes reported as high as 500 to one. But they are fighting a hydra. For every female scout they capture, twomore take her place. The demographic shift becomes undeniable. As the male population of the Vietkong is decimated by Australian firepower and American B-52s, the women step up.

Historical fiction novels

By 1969, in some local guerilla units, women make up 50% of the effective force. They are no longer just couriers. They are sappers. They are snipers. There is a documented incident where an Australian armored column was halted not by a mine, but by a group of women standing on the road chanting, blocking the tanks with their bodies. The drivers hesitated.

You cannot run over a grandmother with a Centurion tank in front of the world press. The delay allowed the VC main force to escape. It was asymmetrical warfare weaponized through gender. The weak defeating the strong by refusing to play by the strong man’s rules. Time accelerates. 1971. The Australians withdraw. The base at New Dot.

The fortress of order is handed over to the ARVN. Within months, it is stripped. The sandbags rot. The jungle begins to reclaim the perimeter. 1975. The fall of Saigon. The tanks roll into the presidential palace. The war is over. What happened to the women? The narrative in the West ends with the helicopters taking off from the embassy roof.

But for the women of the long-haired army, the silence of peace brought a new kind of struggle. They returned to their villages. The uniform of the revolutionary was traded for the peasants pajamas. But the cost was etched into their biology. Many were barren, their bodies wrecked by years of malnutrition, carrying heavy loads and exposure to Agent Orange.

They had spent their youth in tunnels and cages. They had missed the chance for love, for family. In the new Vietnam, they were hailed as heroes. Statues were built. The heroic mother medal was awarded to women who had lost sons and husbands. But medals do not cure PTSD. Medals do not fix a spine compressed by carrying mortar rounds for a decade.

Women’s history books

And what of the Australians? The SAS veterans returned home to a country that wanted to forget. They were the elite, the best of the best. Yet, they were spat on by protesters or met with an icy indifference. They carried their own ghosts. Decades later in RSL returned in services league clubs across Australia, the stories would come out after the third beer.

They wouldn’t talk about the firefights with the NBA regulars. They would talk about the anomalies. I remember this girl, an old trooper would say, staring into his glass. Tiny thing, New Ding Hills, 66. We had her. Could have killed her, didn’t. What happened to her? A younger man asks. Handed her over. Never saw her again. The silence that follows is heavy.

It is the silence of moral injury. The realization that their mercy might have been cruer than their violence. that by handing her over to the machinery of the South Vietnamese state, they condemned her to a hell they washed their hands of. This brings us to the resolution. The capture of female Vietkong by the Australian SAS was a microcosm of the entire war.

It was a collision of high-tech proficiency and low tech endurance. It was a tactical success. The intelligence was gained. The supply lines were cut that amounted to a strategic failure. You can map the tunnels. You can capture the couriers. You can win every single engagement in the bush. But you cannot bombard a belief system into submission.

The Australian SAS were the most effective jungle fighters of the 20th century. They did their job with lethal perfection, but they were deployed to solve a political problem with a military tool. They were trying to catch water with a net. The women they captured were the water. They flowed through the gaps.

They evaporated and condensed somewhere else. October 26th, present day. The Newi den hills. The jungle has healed. The bomb craters are now fish ponds. The defoliated slopes are green again, covered in cashew plantations and acacia trees. The scars of the earth have vanished under the relentless growth of the tropics.

Military history books

We return to the stream where the patrol first saw the girl. The rock is still there. The water still flows clear and cool. There is no rustle of bamboo, no snap of a twig, no silent hand signals. A group of hikers is walking the trail. Young Vietnamese born long after the last Huey departed. They are laughing, taking selfies.

They do not know that 50 years ago on this spot, a 19-year-old girl fought for her life against five giants painted in green and black. The history is under their feet, buried in the laterite. The story of the female Vietkong and the Australian SAS is not a story of good versus evil. It is a story of collision.

It is a story about what happens when the irresistible force of a modern army meets the immovable object of a people defending their home. The Australians left, the women stayed, and in the end, the land remembers who belongs to it. The wind shifts in the canopy. For a second, it sounds like the distant beat of a rotorblade, but it is just the wind.

Silence.

Discover more

Viet Cong tactics

Women in war

Radio communication gear

Camping equipment

Navigation tools

Women’s history books

Elite soldier biographies

Australian military documentaries

Female soldier stories

Vietnam War memorabilia