The 1.4-Mile Shot They Said Couldn’t Be Done

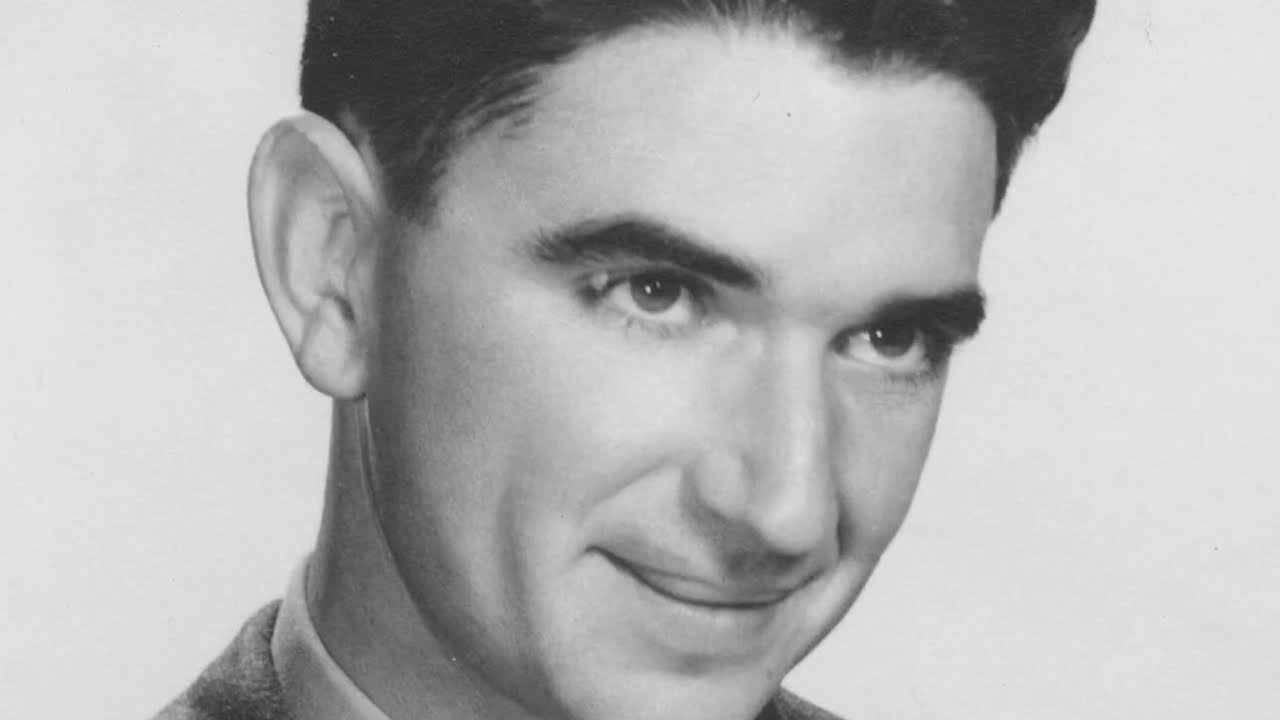

Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock wasn’t used to the feeling—fear. By the summer of 1967, he was America’s most dangerous sniper. Possibly the best in the world. The Viet Cong called him the White Feather. Now, he stood frozen over the body of a Marine next to a spent .30 caliber round. Someone was sending him a message.

It was the signature of Cobra—a North Vietnamese sniper handpicked to hunt the White Feather. Cobra was a ghost: a feral predator who lived off snakes and insects, vanishing into the jungle for months at a time. He was relentless. Obsessed. He left a trail, baiting Hathcock into the jungle.

Discover more

Soldier uniform replicas

Canadian military history

Hollywood News updates

Military strategy guides

televise

Famous quotes posters

Artillery fire simulation

Celebrity news digest

Uncategorized news feed

True crime documentaries

Fueled by vengeance, Hathcock and his spotter, John Burke, took the bait. As they crawled across the jungle floor, a rifle cracked. Burke immediately hit the ground. The greatest American sniper had fallen right into Cobra’s trap. Neither was likely to miss their next shot. But only one would get to pull the trigger first… Born to Snipe From as early as he could remember, Carlos Hathcock believed he was born for war.

It ran in his blood—his father had been a decorated soldier in World War 2. After the war, he returned home and handed three-year-old Carlos a German Mauser rifle as a souvenir. Poverty shaped Carlos’s boyhood. He hunted rabbits, tortoises, and small birds to help feed his family, and by the age of eight, he was already a crack shot. He rarely missed.

He was obsessed with the Marine Corps. When people asked what he wanted to be, he’d answer without hesitation: a Marine. On his twelfth birthday, recognizing this was more than a boy’s fantasy, his mother gave him a 12-gauge shotgun. With it, he could hunt larger game, but something felt wrong.

No matter how hard he tried, the spread and power of the shotgun didn’t suit him. He missed more often. The rifle, he realized, had always been his true weapon. He wasn’t about to let that gift go to waste. At fifteen, he dropped out of high school and went to work for a concrete contractor, mixing and shoveling cement ten hours a day, six days a week.

The job felt miles away from the life he wanted, but without knowing it, Carlos was forging the endurance that would set him apart. The day he turned seventeen in 1959, he walked straight into a Marine recruiting office. His mother signed the enlistment papers. She knew there was no stopping him. At five-foot-ten and 140 pounds, Hathcock was wiry but tough.

Discover more

Contact page service

World War Two documentaries

Military strategy guides

News website template

The Cotton Club

Veteran support services

Vintage clothing

True crime documentaries

Stars news articles

Hollywood News updates

He could run for hours, haul more than his weight, and endure the discomfort that broke other recruits. While others cracked under the pressure of boot camp, Carlos thrived. He wasn’t a standout yet, but he absorbed punishment in silence, never drawing attention. After basic training, he was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines—the “Magnificent Bastards”—and stationed in Hawaii.

He served as a machine gunner. It wasn’t sharpshooting, but Carlos quickly developed a reputation for uncanny accuracy, even behind a machine gun. In 1962, his path took an unexpected turn. He was transferred to Cherry Point, North Carolina—an air base with little use for infantry. They offered him a job handing out basketballs at the gym.

Instead of sulking, he asked a simple question: Did they have a rifle range? They did. Carlos had already competed in marksmanship events in Hawaii, trained under Gunner Arthur Terry, and attended a local sniper school. But it was at Cherry Point that his true skill caught the eye of the base shooting team.

Within a year, he scored 248 out of 250 on the Marine Corps “A Course”—a record never matched again. His precision wasn’t bravado. It was muscle memory, discipline, and relentless repetition. While others relaxed after hours, Carlos practiced—over and over—until even the punishing Rice Paddy Squat position became second nature.

From 1962 to 1965, Hathcock climbed through the ranks of Marine marksmen. He became a Distinguished Marksman, competed in Marine Corps, Interservice, and National Championships, and earned his place among the best. But it still wasn’t enough. The Wimbledon Cup Each year, the epicenter of competitive shooting in the U.S.

is found at Camp Perry, Ohio. Tucked along Route 2 near Lake Erie’s southern shore, it appears on the map as little more than a red square. Yet to marksmen—military or civilian—it is sacred ground. The Wimbledon Cup stands as the crown jewel. A 1,000-yard National High-Power Rifle Championship demands technical perfection, brutal discipline, and the ability to remain calm under immense pressure.

On August 25, 1965, Carlos Hathcock lay prone alongside 130 shooters, all staring downrange at a bull’s-eye no bigger than a pinhead to the eye. Inside the 36-inch target lay a 20-inch white circle—the v-ring. Scores alone didn’t crown champions; the v-count shots within that white center separated the great from the best.

Competitors had 10 rounds and 10 minutes. Most scored a perfect 50. But one shot outside the black, and a year’s dream vanished. Captain Jim Land, Hathcock’s teammate on the Marine Corps Rifle Team, watched as the young corporal worked his way through the ranks. Nearly 3,000 shooters were competing for just 20 final spots.

By day’s end, only Hathcock and Sergeant Danny Sanchez remained from the Marines. August 26 arrived with punishing winds. At 1,000 yards, bullets drifted over 200 inches off course. Twenty finalists lay prone for the sudden-death relay: ten with bolt-actions, ten with semiautomatic service rifles vying for the Farr Trophy. Marine Corps Commandant General Wallace M.

Greene Jr. watched in silence. Before the match, he had told Hathcock and Sanchez: (QUOTE): “You’ve got 196,000 Marines counting on you.” Hathcock entered what he called his “bubble,” shutting out the world. An instructor familiar with his methods once said: (QUOTE) “An elephant could crap on Hathcock’s head, and unless the load blocked the SS, Carlos would never even notice.

” His eyes tracked the mirage, the shimmering heat distortions that revealed wind shifts. Twenty red flags posted every hundred yards snapped in the crosswind. Hathcock whispered: (QUOTE): “If the flag drops, I’ll shoot. If not, hold left—just a hair.” The command crackled over the loudspeaker: (QUOTE) “Gentlemen, you may load one round.

” He picked up a single .300 Winchester Magnum cartridge, chambered it, and nestled it into the stock. For nearly two minutes, he waited. The wind paused. He fired. Silence. The targets were pulled. Then: (QUOTE) “Ladies and gentlemen, we will now disk all misses… There are no misses.” Applause rippled across the stands.

Next came the fives. Then the Vees. Hathcock’s target rose, a white disk square in the center: a V-ring hit. He was still in. He loaded again. This shot felt solid—textbook squeeze, clean timing. In his data book, “14-L” is used for windage. The nerves faded. The crowd disappeared: (QUOTE) “Cease-fire.

” Targets down. Scored. Two threes, four fours. Hathcock’s: another V. Seven shooters remained. In round three, the wind steadied, but nerves frayed. One man fired early. Then Sanchez. Hathcock waited. At 15 seconds remaining, the flag dipped slightly. He adjusted and fired: (QUOTE) “Cease-fire.” No misses, no threes, no fours.

Four shooters failed to hit the V-ring. Only three remained: Hathcock, Sanchez, and one other. The final round. Sanchez fired. Then, the third man. Hathcock waited, tracking the flags. Under twenty seconds left—the flag fluttered. He fired. Silence again. Two targets emerged less; they were less than 3 inches off the bull’s eye.

A pause. The announcer’s electrifying voice came back: (QUOTE) “The 1965 National Champion: Marine Corporal Carlos N. Hathcock II of New Bern, North Carolina,” He was officially the best shot in America. The Child Incident The applause at Camp Perry had barely faded when Hathcock returned to the Marine Corps—only to be sent halfway around the world.

Vietnam was unraveling by the day, and the military needed men like him. By early 1967, Hathcock was on the ground in I Corps, South Vietnam. His reputation preceded him—one of the best marksmen in the Corps. But not everyone was convinced his range of skills would translate to the battlefield. He arrived with his Model 70 Winchester and a white feather tucked into his hatband.

His first test came fast. On a sunbaked road near Đức Phổ, he spotted a boy pushing a bicycle. Maybe twelve years old. Bone-thin shirt plastered to his back with sweat. But it wasn’t the boy that drew Hathcock’s eye—it was the cargo. Four rifles dangled from the handlebars. Three more were strapped beneath the seat.

A bulging haversack swung from the frame, heavy with ammunition. Banana-curved magazines spilled from beneath the flap. The boy was a resupply mule for the Viet Cong. Hathcock’s expression hardened. The VC used children often—they carried rifles and planted mines.

If they didn’t survive their missions, it was the Americans who bore the moral weight. He didn’t want to shoot. That boy might’ve been the same age as his son back home. But those weapons would be in enemy hands by sundown. Marines’ lives were at risk. His Marines. He didn’t aim at the boy. He aimed at the bike—two thousand yards, a broadside shot.

The trigger snapped. The two-and-a-half-inch round tore through the front fork, and the bicycle crumpled. The boy flew forward, hitting the dust in a tumble. The load scattered—rifles, magazines, bandoleers spinning through the air. For a second, there was hope. Maybe the kid would run.

Maybe he’d drop the mission and scatter like a spooked deer. Instead, the boy rolled onto his stomach, grabbed an AK, and jammed in a mag like he’d done it a hundred times. The stock came to his shoulder. Hathcock squeezed off a second shot. A Marine patrol swept in later to recover the cargo. The broken bike was gone by morning.

Hathcock took to his logbook. The sniper’s ritual. Time, location, round used, enemy KIA. Standard. But it wasn’t standard. He’d remember the boy’s