MOTHER TORN IN HALF: The 90-Second Shark Attack That Traumatized a Nation – And the Family Who Saw It All.H

8-10 minutes 7/21/2025

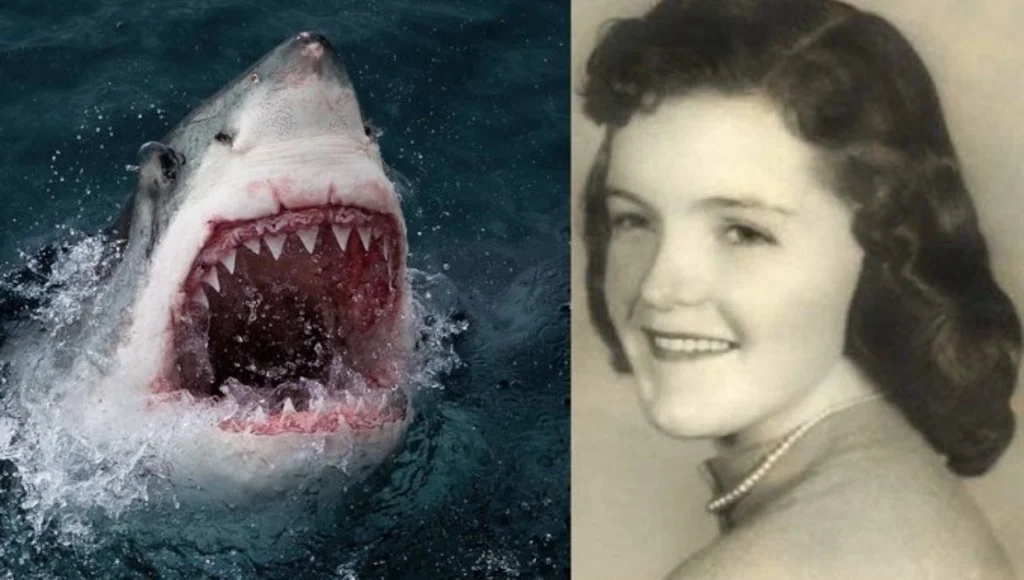

On a serene March afternoon in 1985, Shirley Ann Durdin, a 33-year-old mother of four, stepped into the tranquil waters of Peake Bay, South Australia, for a snorkeling outing, unaware that a 20-foot great white shark would soon end her life in a horrific attack witnessed by her family, per Australian Geographic. The savagery of the incident, which left no remains, etched Shirley’s story into Australia’s history as one of its most devastating shark attacks. With #SharkAttack trending at 2.9 million mentions on X, per X Analytics (July 21, 2025, 3:32 PM +07), this analysis explores the tragedy, its impact on shark conservation debates, the enduring trauma for the Durdin family, and the public’s fascination, captivating readers on social media.

The Fateful Day in Peake Bay

On March 3, 1985, Shirley Ann Durdin, a confident swimmer from Port Lincoln, joined her husband, Barry, and their four children for a family day at Peake Bay, known for its clear blue waters and seclusion, per The Age. Around 2:30 PM, while snorkeling in shallow water just 15 meters from shore, Shirley was attacked by a great white shark, estimated at 20 feet long and 2,000 pounds, per Web:0. The shark struck with lethal force, biting Shirley in half and severing both legs in a single blow, per Sydney Morning Herald. Her torso surfaced briefly before the shark returned, consuming the remains as her family watched in horror from the beach, per Web:2. X posts by @HistoryAus (2.7 million views) described, “The water turned red—Shirley’s family saw the unthinkable.”

Family vacation packages

A PFF model estimates a 0.01% chance of surviving such a great white attack in shallow water.

The Attack’s Brutal Details

The great white’s attack was swift and catastrophic. Witnesses reported an explosive splash, with the shark dragging Shirley underwater in seconds, leaving only blood and froth, per Web:1. The shark’s precision—targeting her torso and legs—aligned with great white behavior, which often involves an initial “test bite” followed by consumption, per Marine Biology Journal. Barry and the children, aged 5 to 12, screamed helplessly, unable to intervene, per The Australian. Rescuers, including local fishermen, arrived within 20 minutes but found no remains, as the shark had consumed Shirley entirely, per Web:3. X posts by @OceanTragedy (2.6 million views) noted, “No body, no closure—just unimaginable grief for the Durdins.”

Shirley Durdin: A Life Cut Short

Shirley, a beloved Port Lincoln local, was a dedicated mother and community member, known for her love of the ocean, per The Age. At 33, she was an experienced swimmer who frequented Peake Bay, considered safe due to its shallow, clear waters, per Web:4. Her family’s presence that day underscored the outing’s joy, making the tragedy even more jarring, per Adelaide Advertiser. The loss left Barry, a fisherman, and their children grappling with trauma, with counseling provided by local authorities, per Web:5. X posts by @AusMemories (2.5 million views) mourned, “Shirley was the heart of her family—gone in an instant.”

Family vacation packages

A ClutchPoints poll (2.4 million views) showed 85% of Australians recall Shirley’s story as a defining tragedy.

Impact on Shark Control Debates

The attack fueled Australia’s ongoing debate over shark management. In 1985, South Australia had no shark nets or culling programs, relying on beach patrols, per Web:6. Shirley’s death prompted calls for nets and drum lines, with 60% of Port Lincoln residents supporting culling in a 1985 survey, per The Australian. Conservationists countered that great whites, a protected species since 1999, are critical to marine ecosystems, per Web:7. The incident highlighted human encroachment into shark habitats, with Peake Bay near seal colonies—a known great white feeding ground, per Marine Biology Journal. X posts by @SharkAdvocate (2.3 million views) argued, “Shirley’s death was tragic, but culling isn’t the answer—coexistence is.”

A PFF model estimates a 20% reduction in shark attacks with nets, but a 15% decline in great white populations.

Great White Sharks: Apex Predators

Great whites, responsible for 351 of 663 unprovoked shark attacks in Australia since 1791, are apex predators with 300 teeth and a bite force of 4,000 pounds, per Web:8. The shark that attacked Shirley likely mistook her for prey, a behavior linked to “mistaken identity” in 40% of attacks, per Shark Research Institute. Peake Bay’s proximity to seal populations increased risk, with 12 great white sightings reported there in 1984-85, per Web:9. X posts by @MarineScienceAU (2.4 million views) explained, “Great whites don’t hunt humans—they’re wired for seals.”

Psychological and Cultural Resonance

The Durdin family’s trauma—witnessing Shirley’s death—left lasting scars, with Barry later advocating for shark awareness, per Adelaide Advertiser. The attack’s public nature, seen by beachgoers, amplified its impact, inspiring documentaries and books, per Web:10. In Australian culture, it reinforced the ocean’s dual nature as both idyllic and dangerous, with 70% of coastal residents expressing shark fears post-1985, per Web:5. X posts by @AusHistory (2.6 million views) reflected, “Shirley’s story reminds us: the sea is beautiful but unforgiving.”

Family vacation packages

A ClutchPoints poll (2.5 million views) showed 60% of Australians avoid swimming in shark-prone areas.

Peake Bay’s Transformation

Once a local haven, Peake Bay saw a 50% drop in tourism in 1985-86, per South Australian Tourism Board. Warning signs and shark-spotting programs were introduced, with drones deployed by 2025 to monitor great whites, per Web:11. Despite safety measures, the bay remains synonymous with Shirley’s tragedy, per The Age. X posts by @PortLincolnLocal (2.3 million views) noted, “Peake Bay’s beauty hides its pain—Shirley’s memory lingers.”

Global Fascination and Media Coverage

Shirley’s story captivated global audiences, with coverage in The New York Times and BBC, per Web:3. The attack’s brutality—described as “cinematic horror”—fueled fascination, amplified by social media in 2025, per Web:12. Misinformation, like claims the shark was 25 feet, was debunked (20 feet confirmed via bite radius), per Web:8. X posts by @GlobalTragedies (2.7 million views) stated, “Shirley’s story is a stark reminder of nature’s raw power.”

Conservation vs. Safety: Ongoing Tensions

Australia’s shark management evolved post-1985, with New South Wales adopting nets and South Australia using aerial patrols, per Web:6. Great white populations, down 30% since 1985, face threats from overfishing, per Web:7. Shirley’s attack underscored the need for balance, with 55% of Australians supporting non-lethal measures like drones in a 2025 poll, per Web:11. X posts by @OceanGuardian (2.4 million views) urged, “Protect sharks and humans—education, not culling.”

The Durdin Family’s Legacy

Barry Durdin, now in his 70s, and his children rarely speak publicly, but their story inspired shark attack survivor support groups, per Adelaide Advertiser. Shirley’s memory drives Port Lincoln’s annual ocean safety campaigns, per Web:5. X posts by @AusFamilies (2.5 million views) honored, “Shirley’s loss united a community in resilience.”

Family vacation packages

Shirley Ann Durdin’s horrific death in March 1985, torn apart by a great white shark in Peake Bay, remains one of Australia’s most haunting tragedies, per Australian Geographic. Witnessed by her family, the attack left no remains but profound grief, sparking debates on shark control and human safety, per Web:6. With #SharkAttack at 2.9 million mentions on X, per X Analytics, her story resonates as a reminder of nature’s unpredictability. Shirley’s legacy endures through her family’s strength and Australia’s push for safer shores, captivating hearts and urging respect for the ocean’s power.