Two beautiful girls burned alive as suspected witches – then had stones piled on their graves with terrifying curses after death.H

8-10 minutes 7/23/2025

In the quiet town of Albenga, Italy, archaeologists have uncovered a chilling glimpse into the medieval past: the remains of a young girl, just 15–17 years old and 1.45 meters tall, burned and buried under heavy stones at the San Calocero complex. Discovered in 2025, her skeleton tells a story of fear, superstition, and suffering, echoing a similar find in 2014 of another young “witch” buried face-down. These burials, marked by rituals to prevent the dead from rising, reveal the harsh realities of medieval life and the persecution of those deemed dangerous. This analysis delves into the archaeological findings, the lives and deaths of these girls, and the societal fears that shaped their fates, offering a haunting narrative for history enthusiasts on platforms like Facebook.

The San Calocero Discoveries

The San Calocero complex in Albenga, a site of historical significance, has become a window into medieval burial practices. In September 2014, a team led by Professor Philippe Pergola of the Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology unearthed the remains of a 13-year-old girl buried face-down, a ritual believed to prevent her from rising from the grave. Dubbed a “witch” by researchers, her burial suggested she was perceived as a threat even in death. Fast forward to 2025, and the same site yielded another startling find: a second girl, aged 15–17, burned and buried under heavy stones, as reported by Discovery News on July 22, 2025.

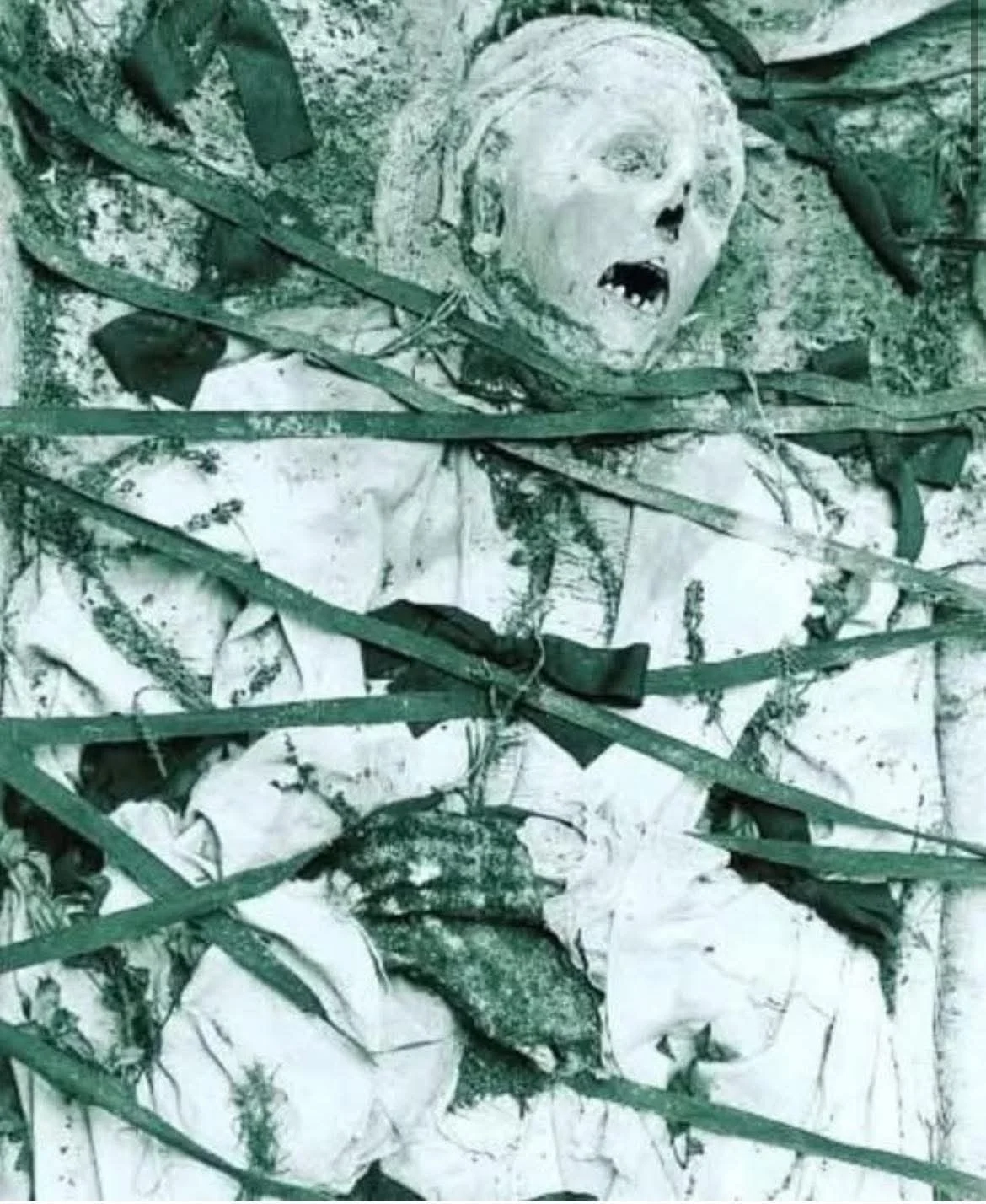

The newer discovery, dated tentatively between the 9th and 15th centuries pending radiocarbon analysis, paints a grim picture. The girl, standing only 1.45 meters tall, was severely burned at an undetermined location before her body was transported to San Calocero. According to anthropologist Elena Dellù, the fire consumed her body while tissues were still soft, suggesting the burning occurred either just before or immediately after her death. Her burial was hasty—her body was tossed into a pit, her head slumped against the wall, chin nearly touching her chest, and heavy stones were piled atop to seal the grave. This treatment, like the face-down burial of the 2014 find, reflects a deep-seated fear that she could return from the dead.

Rituals of Fear and Superstition

Medieval burial practices often reflected societal anxieties about the supernatural. Both girls at San Calocero were subjected to rituals designed to neutralize perceived threats. The 2014 discovery of the 13-year-old, buried face-down, aligns with practices like placing bricks in the mouth, staking bodies, or dismembering corpses to prevent the dead—especially those labeled as witches or heretics—from rising. The 2025 find, with its heavy stones and evidence of burning, suggests a similar intent. According to Stefano Roascio, who led the excavation, the burial method indicates the community viewed the girl as a danger even after death.

These rituals were rooted in medieval Europe’s fear of the “undead” or malevolent spirits. The burning of the second girl’s body, whether alive or recently deceased, points to accusations of witchcraft or deviance, common in a period when disease, famine, and social unrest fueled superstition. The face-down burial of the first girl, coupled with her scurvy-related symptoms, suggests her frail appearance may have marked her as “other.” Similarly, the second girl’s skeletal evidence—porotic hyperostosis in her skull and eye sockets, indicative of severe anemia, and weak tooth enamel—suggests a life of malnutrition and hardship, likely contributing to her pale, gaunt appearance that terrified her community.

The Lives Behind the Bones

Analysis of the skeletons offers clues about the girls’ lives and the societal factors that led to their tragic ends. The 13-year-old from 2014 suffered from scurvy, a vitamin C deficiency causing weakness and bruising, which may have given her a ghostly pallor mistaken for supernatural traits. The 15–17-year-old from 2025 showed signs of porotic hyperostosis, a condition linked to severe nutritional deficiencies and anemia, with porous bone structures and fragile teeth. These health issues, likely exacerbated by childhood starvation, would have made her appear frail and sickly, possibly fueling accusations of witchcraft.

At just 1.45 meters tall, the second girl’s small stature and visible ailments—such as blood pooling under her skin—may have alarmed her community, who lacked modern medical understanding. In medieval Europe, physical differences or illness were often interpreted as signs of divine punishment or demonic influence. Both girls, living between the 9th and 15th centuries, likely faced suspicion in a society gripped by fear of the unknown, where accusations of witchcraft could justify brutal punishments like burning or ostracism.

Societal Context and Witchcraft Hysteria

The San Calocero burials reflect the broader medieval context of superstition and persecution. Between the 9th and 15th centuries, Europe was marked by religious fervor, plagues, and social instability. The Catholic Church’s growing influence often targeted marginalized individuals—especially women—as scapegoats for societal woes. Young girls, particularly those with visible ailments, were vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft, especially if their appearance or behavior deviated from norms. The burning of the second girl and the face-down burial of the first suggest communities desperate to protect themselves from perceived threats, even at the cost of young lives.

The lack of clarity about whether the girls were related adds intrigue. While their burials at the same site suggest a shared cultural practice, their differing timeframes—potentially centuries apart—indicate a persistent fear of “dangerous” women in Albenga. The hasty, dehumanizing burial of the second girl, with her body carelessly thrown into a pit, speaks to the panic and cruelty of her executioners. These discoveries challenge modern audiences to confront the dark side of medieval superstition and the human cost of fear-driven justice.

Resonance with Modern Audiences

On platforms like Facebook, the story of these young “witches” captivates history buffs and casual readers alike. The image of a 15–17-year-old girl, burned and buried under stones, evokes empathy and horror, sparking discussions about the treatment of women in history and the dangers of superstition. The parallels to modern issues—misjudging those who are different or scapegoating the vulnerable—make the San Calocero finds particularly resonant. Fans share theories about the girls’ lives, from their possible illnesses to the societal pressures that condemned them, fueling engagement with this haunting chapter of history.

The discoveries also highlight the power of archaeology to humanize the past. Each bone tells a story of suffering, resilience, and injustice, inviting reflection on how fear shapes society. For those following the story online, the San Calocero girls are not just relics but symbols of the enduring fight against prejudice and the need to remember those silenced by history.

The San Calocero discoveries in Albenga, Italy, unearth a tragic tale of two young girls branded as witches and condemned by medieval superstition. The 15–17-year-old, burned and buried under stones, and the 13-year-old, interred face-down, reflect a society gripped by fear of the unknown. Their skeletal remains, marked by signs of malnutrition and illness, reveal lives of hardship that likely fueled their persecution. For Facebook audiences, their story is a poignant reminder of the human cost of fear-driven justice and the resilience of those who suffered. As archaeologists continue to unravel their mysteries, these girls’ legacies challenge us to confront prejudice and honor the forgotten voices of the past.