Why Spruance Refused to Chase Japanese After Midway – Halsey Would’ve Pursued

Rear Admiral Raymon Spruce stood on the bridge watching the horizon. Four Japanese carriers were burning. Akagi Kaga saw you hear. The most powerful carrier force ever assembled was going to the bottom of the Pacific. The Battle of Midway was won. Below decks, Admiral Holse’s staff officers were celebrating.

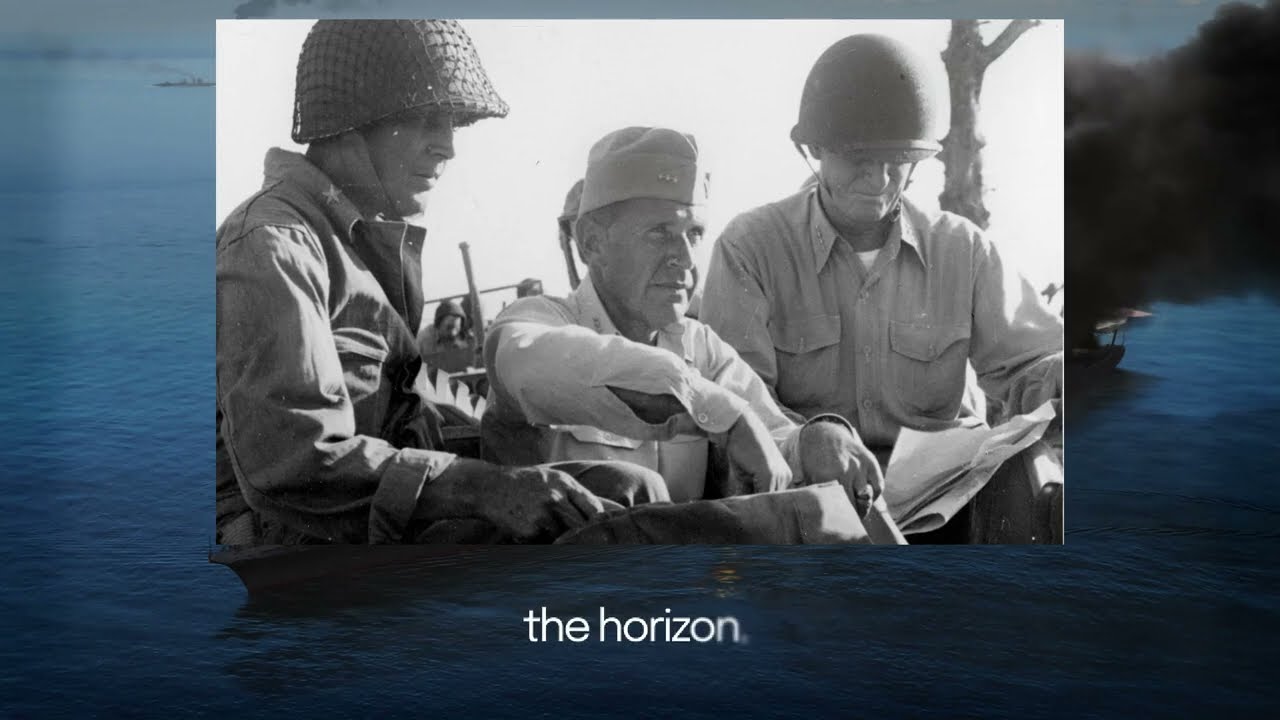

They’d been assigned to Spruce when Holsey fell ill with a skin infection days before the battle. They’d watched Spruent fight brilliantly, coordinated the strikes, timed the attacks perfectly, destroyed four carriers. Now they wanted him to finish the job. Captain Miles Browning, Holse’s chief of staff, came to the bridge.

Discover more

mirrors

television

Bruce Lee martial arts films

Historical fiction novels

Action movie Blu-rays

Documentaries about gangsters

Entertainment news magazine

News website subscription

PACKARD

Celebrity gossip news

He brought charts, calculations, estimates of Japanese fleet positions. The Japanese had more ships out there, battleships, cruisers, transports carrying invasion troops, all retreating west toward Wake Island. American carriers could catch them by dawn, launch strikes at first light, sink everything that remained of the invasion force.

It was the aggressive move, the killer instinct, what Admiral Hulsey would have done without hesitation. Browning laid out the plan. The fleet would steam west at maximum speed, close the distance overnight, hit them at sunrise when they were most vulnerable. Other officers joined in. Commander Bill Baracka, Commander Thomas Jeter, all Holse’s men, all urging pursuit.

They’d seen Holsey operate, knew how he thought. This was the moment to chase, to destroy, to turn victory into annihilation. Spruent listened to all of them, studied the charts, asked questions about Japanese positions. Then he said, “No, turn the fleet east, away from the enemy, returned to defensive positions around Midway.

” The staff officers were stunned. They argued, pushed back, explained that every hour they waited, the Japanese got farther away. This was the chance to end Japanese naval power in the Pacific. Sink their battleships, sink their transports, make sure they never threatened Midway again. Spruce’s response was quiet. Final. I’m not Admiral Holsey. Then he gave the order.

The fleet turned east away from Glory toward Caution. Browning went to his quarters, furious. started writing a report for Hoy documenting everything Spruce had done wrong. This is the story of the most controversial decision at Midway when Raymond Spruce refused to chase a beaten enemy when playing it safe became the right move and when the difference between Hulsey and Spruants determined who would be remembered as the better admiral.

Discover more

mirrors

Documentaries about gangsters

Action movie Blu-rays

Soldier life stories

WWII history tours

Military history books

Detective novels subscriptions

Historical fiction novels

Model airplanes tanks ships

Bruce Lee martial arts films

To understand why Spruce refused, you need to understand what he knew. Four Japanese carriers were sunk. That was victory. But it wasn’t the whole story. The Japanese had come to Midway with over 200 ships. The carrier force was just one element of a massive operation. Admiral Yamamoto commanded the main fleet. Seven battleships, including Yamato, the largest battleship ever built.

18-in guns that could sink a carrier with a single salvo. Those battleships were somewhere west, trailing behind the carriers. Maybe a 100 miles away. maybe 200. Spruce’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Commander Edwin Leighton, had briefed him on the composition of Yamamoto’s force. Battleships, heavy cruisers, light cruisers, dozens of destroyers, all built for surface combat, all experienced in night fighting.

If Spruce chased west, he’d be sailing toward that force. At night, American carriers were powerful in daylight. Launch aircraft at dawn. Strike from 200 m away. Stay out of gun range. In darkness, they were floating targets. No way to launch aircraft in the dark. Not in 1942. Night carrier operations were still experimental.

If Japanese battleships got within gun range, the carriers would die. One salvo from Yamato could a carrier. Two salvos would sink one. And the Japanese had more than battleships. They had destroyers equipped with longlance torpedoes. The best torpedoes in the world. Range of 20 m. Weightless. nearly impossible to spot at night.

Japanese destroyers could launch torpedoes at the American carriers from positions the Americans couldn’t even see. Spruce knew all this not from guessing, from intelligence briefings, from his own experience commanding cruisers. He understood night combat. Understood what happened when you sailed into enemy waters in the dark. You died, so he turned east.

Discover more

mirrors

PACKARD

Historical fiction novels

Navy SEAL stories

Self-defense courses

News advertising space

Documentaries about gangsters

television

Military gear replicas

News content creation

Holse staff didn’t see it that way. Captain Miles Browning was Holsey’s chief of staff. He’d been planning aggressive carrier operations for months. Browning argued that the Japanese were beaten, demoralized, retreating in disorder. This was the moment to destroy them completely. Sink the battleships. Sink the transports.

End Japanese naval power in one stroke. Spruent listened. Didn’t argue. Just said no. The fleet would withdraw to defensive positions. Cover midway. wait for the Japanese to either attack again or retreat. Browning was furious. He went to his quarters and wrote a report for Holsey. Detailed everything Spruent had done wrong. How Spruent had let the Japanese escape.

How a real carrier admiral would have pursued. Holsey read that report weeks later. From his hospital bed in Pearl Harbor, his response surprised everyone. Spruants did exactly right. Holsey understood something Browning didn’t. Something most aggressive commanders never learn. Knowing when not to fight is harder than knowing when to fight.

The Japanese fleet did retreat west, but not in disorder. Yamamoto positioned his battleships between the American carriers and the retreating transports. He was hoping Spruce would chase. Had planned for it. Japanese destroyers and cruisers were spread out, ready to launch torpedo attacks at night. The battleships were ready to engage any American ships that came in range.

If Spruce had pursued, the American carriers would have sailed into a killing zone. At night, American advantages disappeared. Radar helped, but wasn’t decisive yet. Not in 1942. The Japanese had better optics, better torpedoes, more experience in night combat, and the American carriers would have been the targets.

Three carriers, Enterprise, Hornet. Yorktown was already crippled. Losing even one carrier in a night action would have turned victory into disaster. Spruent knew this not from intelligence, from judgment. He was a cruiser admiral. Had spent his career on surface ships. Understood what battleships could do in the dark. Carriers needed daylight.

Needed to launch strikes from a distance. Getting close to enemy battleships at night was suicide. So he turned east. The Japanese kept retreating. Yamamoto canled the midway operation. and the entire fleet withdrew to Japan, Spruance’s carriers were untouched, ready for the next battle. That was the victory. Not sinking more ships, preserving the fleet. But Ho’s staff never accepted it.

For weeks after Midway, they grumbled. Spruce had been too cautious, had lacked the killer instinct. If Hoy had been there, they said the Japanese fleet would have been annihilated. Maybe, maybe not. Two years later, Holsey got his chance to show what aggressive pursuit looked like. October 1944, the battle of Lee Gulf.

Holsey commanded the third fleet. The most powerful naval force in history. 16 fleet carriers, eight light carriers, hundreds of aircraft. The Japanese Navy sorted for one last desperate gamble. Three separate forces converging on the American landing at late. The Northern Force was built around four carriers, almost no aircraft. It was a decoy.

The center force was the real threat. Battleships including Yamato, cruisers, destroyers heading for the landing beaches. Holse’s job was to protect the landings. Stop the center force. Instead, he chased the carriers. The Japanese northern force appeared north of the Philippines. Holse scouts spotted the carriers, reported their position.

Holsey made his decision instantly. Take the entire third fleet north. Destroy the Japanese carriers. His staff pointed out that the center force was still a threat, still heading toward the landing beaches. Holsey didn’t care. The carriers were the priority. The battle wagons could be handled by other forces.

He sent his entire fleet north. Every carrier, every battleship, every escort, left nothing to guard San Bernardino straight. The center force came through unopposed, headed straight for the landing beaches. Only a handful of escort carriers and destroyers stood between Yamato and MacArthur’s forces. Taffy 3.

Task unit 77.3.3. Six escort carriers, seven destroyers and destroyer escorts commanded by Rear Admiral Clifton Sprag. No relation to Raymond Spruants, but about to face the same kind of decision. Fight or run. At 6:45 a.m. on October 25th, Sprag’s lookout spotted Pagodamasts on the horizon.

Japanese battleships coming fast, led by Yamato. Sprag ordered his carriers to run, launch everything they had, every fighter, every bomber, even aircraft that weren’t armed. Then he ordered his destroyers to attack. It was suicide. Destroyers charging battleships, but it was the only chance the carriers had. USS Johnston charged first.

Commander Ernest Evans pushed his destroyer to flank speed, headed straight for the Japanese fleet. Johnston fired all her torpedoes at 10,000 yards, then stayed in close, firing her 5-in guns at battleships and cruisers. The Japanese concentrated fire on Johnston. Shells ripped through her hole, knocked out her engines, killed her steering.

Evans kept fighting, manually controlling the guns, firing until Japanese shells tore Johnston apart. USS Hull did the same, charged the Japanese line, took over 40 major caliber hits, sank, still firing. USS Samuel B. Roberts, a destroyer escort, went after Yamato herself, a 1,700 ton ship charging a 72,000 ton battleship.

She fired 600 rounds from her 5-in guns before being blown apart. The carriers were running at maximum speed, making smoke, praying. For two hours, the Japanese chased them. Yamato’s 18-in guns fired at the escort carriers from 20,000 yards. They should have hit, should have sunk every carrier. But the smoke screens worked. The desperate aircraft attacks disrupted Japanese formations.

And the Japanese commander made a mistake. He thought he was fighting Holse fleet carriers. Thought the real American carriers were nearby. He got cautious, started maneuvering defensively. Then inexplicably, he ordered a retreat. The center force turned around, went back through San Bernardino Straight. They’d been minutes from destroying Taffy 3, minutes from shelling MacArthur’s landing beaches, but they retreated.

Sprag’s escort carriers survived barely. That’s what happened when someone did what Ho’s staff wanted Spruants to do at Midway. Sail toward enemy battleships. Hope you can survive the night. Hope the enemy makes mistakes. Taffy 3 survived because the Japanese commander got cautious. If Spraw had chased at Midway, Yamamoto wouldn’t have gotten cautious.

He’d have been waiting for the American carriers with his entire fleet. Ho’s aggressive pursuit of the Japanese carriers had nearly caused disaster. When Admiral Nimttz found out, he sent Holsey a message. Tur cutting. Where is Task Force 34? The world wonders. It was the closest thing to a public rebuke Nimttz ever issued.

Holsey had chased the decoy, left the vital position unguarded, almost lost the battle because he couldn’t resist pursuing. That’s what Spruants avoided at Midway. Spruce understood that protecting what you have matters more than destroying what you can see. The American carriers at Midway were irreplaceable.

The US had six fleet carriers in the Pacific. Losing one would have crippled American offensive capability for months. Sinking more Japanese ships wasn’t worth that risk. Hulsey never learned that lesson. Even after Lady Gulf, he defended his decision. The carriers were the threat. He argued destroying them was the mission. Nimttz didn’t agree.

Neither did the postwar analysis. Holly had made an emotional decision. Chased the enemy he wanted to fight instead of protecting his objective. Spruce at Midway made a rational decision, preserved his force, secured the victory. The difference came down to temperament. Holy was aggressive, instinctive, trusted his gut, believed in pressing every advantage.

Spruce was cautious, analytical, calculated risks, stopped when the objective was achieved. Both were brilliant admirals. Both won crucial battles, but Spruce won without unnecessary risk. Hoy won despite taking unnecessary risk. In 1942, America needed Spruce’s caution. The carrier force was too small to waste on risky pursuits.

By 1944, America could afford Holsey’s aggression. There were enough carriers to take chances, but even then, Hosey’s instinct to chase nearly caused disaster. After the war, naval historians debated the decision at Midway. Some argued Spruce should have pursued, that more Japanese ships could have been sunk, that the war might have been shortened. Most disagreed.

Admiral Nimmitz wrote in his official report that Spruce’s decision to break off was sound and proper. The risk of night combat with Japanese battleships outweighed the potential gains. Hollyy himself admitted Spruance was right, though it took him years to say it. In a 1947 interview, Holsey was asked what he would have done at Midway.

His response was honest. I would have chased them and I probably would have lost carriers doing it. Ray Spruants was smarter than me. It was the closest Holsey ever came to admitting he wasn’t always right. The irony is that Holsey got the glory while Spruce got the results. Holsey was famous, beloved by the press.

Bull Holsey, the fighting admiral, the man who promised to ride Yamamoto’s horse through Tokyo. Spruce was quiet, professional, avoided reporters, made no dramatic promises. But Spruce’s battles were masterpieces. Midway, the Philippine Sea, Okinawa, calculated, careful, decisive. Holse’s battles were dramatic.

The Solomons, Lee Gulf, aggressive, risky, sometimes brilliant, sometimes nearly disastrous. The Navy needed both kinds of admirals. But when the war was on the line, when losing meant catastrophe, they sent Spruants. At midway, Spruce had already won. Four carriers sunk. The invasion repelled. Chasing west wouldn’t make the victory bigger.

It would only risk making it smaller. So he turned east, let the Japanese retreat, saved his carriers for the next battle. It wasn’t the aggressive move, wasn’t the heroic move, wasn’t what Holsey would have done. But it was right. That’s the difference between good admirals and great ones. Good admirals know how to attack. Great admirals know when to stop.

Spruce stopped at Midway, preserved his force, won the battle without unnecessary risk. Holsey would have chased, might have sunk more ships, might have lost carriers in the dark. We’ll never know for sure. But we know what happened when Holsey did chase two years later. He nearly lost the battle of Lady Gulf pursuing a decoy.

Spruce refused to chase at Midway, avoided that mistake entirely. When Spruce died in 1969, Hulsey was one of the pbearers. He told reporters afterward that Spruce was the best admiral in the Navy. Coming from Holy that meant something because Hollyy knew what he was. Aggressive, bold, willing to take risks.

But he also knew what Spruance was. Careful, calculated, unwilling to gamble when he didn’t have to. At Midway, America needed careful. Spruce gave them careful and won the most important naval battle of the Pacific War without losing a single carrier. That’s not caution. That’s genius. Holsey would have chased. Spruce refused. History proved Sprance