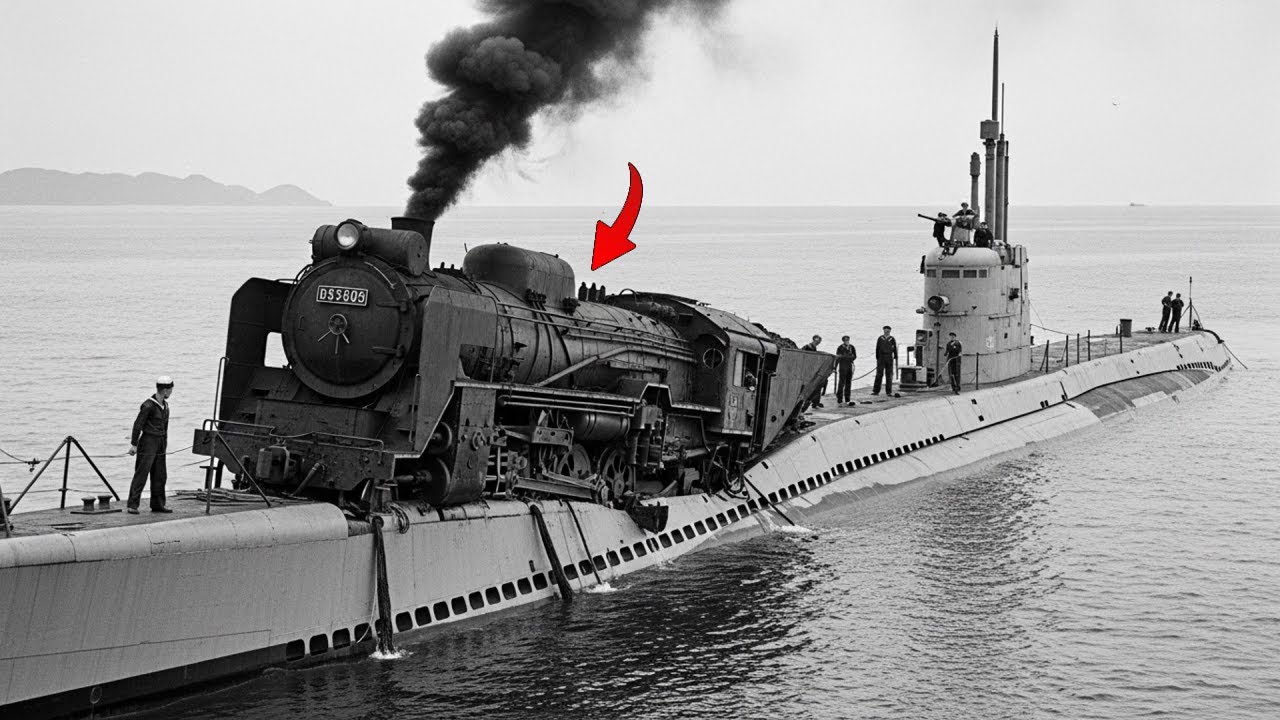

When This Submarine Destroyed a Japanese Train — The Only US Ground Attack on Japanese Soil.H

When This Submarine Destroyed a Japanese Train — The Only US Ground Attack on Japanese Soil

At 0700 on July 19th, 1945, Commander Eugene Flucky pressed his eye against the periscope of USS Barb, watching a Japanese supply train snake along the Kaputo coastline, carrying troops and ammunition that would kill American soldiers if he didn’t stop it. 31 years old, five war patrols as Barb’s commander.

Soldier uniform replicas

17 enemy ships already at the bottom. The Japanese were running six trains per day along that coastal railroad, each carrying between 40 and 60 soldiers plus ammunition and supplies for the garrison at Kashiho. Flucky had been hunting in the Sea of Otsk for 3 weeks. The Gatetoclass submarine USS Barb displaced 2400 tons submerged and carried a crew of 80 men.

Discover more

Contact page service

Hollywood News updates

True crime documentaries

Gangster movie box sets

Detective novels

World War Two documentaries

Stars news articles

Military model kits

Canadian military history

Artillery fire simulation

She was one of the most decorated submarines in the Pacific Fleet, four presidential unit citations, eight battle stars, a Navy unit commenation. But what made Barb truly dangerous wasn’t her awards. It was her captain. 3 months earlier, Flucky had received the Medal of Honor. The citation described his attack on Nam Kuan Harbor off the coast of China in January 1945.

He had taken Barb into water so shallow the submarine couldn’t dive. Minefields on both sides, Japanese destroyers patrolling the entrance. 30 merchant ships anchored inside, protected by what the Japanese believed was an impenetrable defensive position. Flucky attacked anyway. Six torpedoes into the convoy, then four more.

Then a high-speed surface run through uncharted waters while depth charges exploded around them. Eight ships sunk, zero American casualties. The brass in Pearl Harbor called it the most audacious submarine attack of the war. But Flucky wasn’t satisfied. By June 1945, Japanese merchant shipping had nearly vanished from the Pacific.

American submarines were running out of targets. Before Barb’s 12th and final war patrol, Fluki approached the Navy’s research and development staff with an unusual request. He wanted rockets. The Mark 51 launcher held 12 5-in spinstabilized rockets, each tipped with 10 pounds of high explosive, maximum range of 3 mi. The Navy was testing the system as an anti-comicazi weapon for landing ships.

Fluki convinced them to bolt one onto Barb’s forward deck. It made her the only rocket launching submarine in the United States Navy. Barb departed midway on June 8th, loaded with 72 rockets and orders to raise hell along the Japanese coast. She reached the waters north of Hokkaido on June 20th.

2 days later at 0230 on June 22nd, Fluki surfaced 3 mi off the town of Sharie. Population 20,000, a factory district that produced supplies for the Japanese military. The submarine turned broadside to the shore. Fluki gave the order. 12 rockets ripple fired in 5 seconds. They screamed through the darkness and slammed into Charie’s industrial center.

Fires erupted across the waterfront. Barb submerged and disappeared before the Japanese could respond. It was the first time in history a submarine had launched rockets against a shore target. Over the next 3 weeks, Barb fired 60 more rockets at factory towns along the Hokkaido and Karafuto coasts.

Shikuka, Kashiho, Shirtorii. Japan’s largest paper mill destroyed. A leather tanning factory that made pilot uniforms burning. Small shipyards reduced to wreckage. Fluki also used Barb’s 4-in deck gun to shell military installations. The submarine operated with impunity. By mid July, Japanese reconnaissance aircraft were hunting for her, but Fluki kept moving, kept striking, kept the enemy off balance.

Discover more

Rio Bravo

Soldier uniform replicas

Celebrity gossip magazines

Detective novels

Uncategorized news feed

German army history

Canadian military history

Military history books

Soldier bravery stories

News content subscription

Then on July 19th, while patrolling off southern Kataputo, Fluki noticed something through the periscope. A railroad ran within 400 yards of the coastline. Trains moving north and south throughout the day and night. Locomotives pulling freight cars filled with troops and military cargo. The trains represented a supply line feeding Japanese forces preparing to resist an American invasion.

Flucky watched the trains for 3 days. He counted schedules. He studied the terrain. The beach was accessible. The tracks were vulnerable. And an idea began forming. The problem was obvious. Barb could surface and shell the railroad with her deck gun, but that would only damage the tracks. The Japanese would repair them within hours.

What Flucky wanted was to destroy a moving train. Maximum damage, maximum disruption, maximum psychological impact. But submarines didn’t carry weapons designed for land targets. Torpedoes were useless. The rockets lacked the precision for a moving target. The deck gun couldn’t track a train through coastal terrain. Flucky needed a different solution.

Something the Japanese wouldn’t expect. Something no submarine had ever attempted. If you want to see how Flucky solved this impossible problem, please hit that like button. It helps us share more forgotten stories from World War II. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Flucky. On the evening of July 22nd, Chief Gunner’s mate Paul Saunders and electricians mate third class Billy Hatfield sat in Barb’s cramped forward torpedo room with aproblem.

Flucky had asked them to devise a way to blow up a train without risking a shore party during the explosion. Hatfield stared at the 55lb scutling charge. The device was designed to destroy Barb crew had to abandon her to prevent capture. Hatfield had an idea. He remembered a childhood trick. placing walnuts on railroad tracks so the weight of passing trains would crack them open.

What if they could rig the scuttling charge the same way? A micro switch buried under the rails. The weight of a locomotive closing the circuit. The train would destroy itself. Fluki examined the device Hatfield and Saunders had constructed. A simple pressure switch salvaged from submarine components.

Three dry cell batteries wired in series. The 55 pound scuttling charge packed with enough explosive to vaporize a locomotive. The entire assembly fit inside an empty pickle jar for waterproofing. When a train’s weight depressed the rails even a/4 in, the micro switch would complete the electrical circuit. Detonation would occur directly beneath the locomotive’s boiler.

Hatfield estimated the explosion would destroy at least the first three cars and derail everything behind them. The engineering was sound, but the mission itself presented enormous risks. Barb would need to surface within a thousand yards of the Japanese coastline. A shore party would paddle inflatable rafts to the beach, cross 400 yardds of enemy territory, plant the explosive, and return before dawn.

If Japanese patrols discovered them, the men would be trapped on hostile soil with no support and no escape route. If the submarine was spotted while surfaced in shallow water, she couldn’t dive quickly enough to evade attack. Fluki calculated they would have roughly 90 minutes from the moment the rafts launched until Barb had to submerge.

Every man aboard Barb volunteered for the mission. 80 sailors raised their hands when Fluki asked for volunteers. The commander established strict criteria. First, unmarried men only. He refused to create widows. Second, physical fitness and swimming ability. The men would be paddling through surf and might need to swim if the rafts capsized.

Third, preferably former boy scouts. Fluki had been a scout himself and believed their training and navigation and emergency procedures would prove invaluable if the party got separated or lost. Fourth, a mix of skills. He needed an electrician to wire the device, strong men to dig, and experienced sailors who could handle the rafts in darkness.

Flucky selected eight men. Chief gunners made Paul Saunders would lead the shore party. 26 years old, he had served aboard Barb since her commissioning in 1942. Every single war patrol, Atlantic and Pacific. Electricians mate, thirdclass Billy Hatfield would handle the explosive device. He had worked for the railroad before the war and understood track construction.

Signalman secondclass Francis Sever. Ships cook first class Lawrence Nuland. Torpedoman’s mate third class Edward Clinglesmith. Motor machinist mate secondclass James Richard. Motor machinist mate first class John Marcus. And Lieutenant William Walker would serve as the officer in charge. The crew began preparations.

Barb’s engineers cut steel plates from the engine room lower flats, then bent and welded them into improvised picks and shovels for digging. The shore party would need to bury the explosive and batteries at least 6 in beneath the railroad ties to ensure the micro switch function properly. The men packed survival gear in case they had to flee towards Soviet territory on the northern half of Sakalene Island 130 mi through mountain ranges. They also packed raw stakes.

Intelligence reports indicated Japanese patrols used guard dogs along the coastal railroad. The stakes might buy them a few precious seconds if they encountered animals. Weather became the critical factor. Flucky needed cloud cover to hide the 3/4 moon. Clear skies would illuminate the submarine in the rafts, making them visible to Japanese centuries.

For 4 days, Barb patrolled off Kafudo while the crew watched the sky clear, clear again. Flucky grew increasingly frustrated. Only 5 days remained in their patrol schedule. After that, Barb would need to return to Midway. The window was closing. On the afternoon of July 22nd, Cirrus clouds appeared on the horizon. By evening, white stratus clouds were capping the mountain peaks along the Karafuto coast.

A cloud cover was building from the west. Flucky made the decision. They would execute the mission that night. Final preparations accelerated. The shore party checked their equipment. Waterproof flashlights, pistols, the pickle jar containing batteries and explosives, digging tools, May West life vests in case they had to swim.

The two rubber rafts were readied on deck. At 2300 hours on July 22nd, Barb began her approach to the Karafuto coastline. Flucky kept the submarine on the surface, running slowly on electric motors to reduce noise. The skycooperated. Cloud cover obscured the moon. Darkness blanketed the water. Through the periscope, Flucky could see the railroad running parallel to the shoreline.

No lights visible on the beach. No signs of patrol activity. The conditions were as favorable as they would ever be. Barb crept to within 950 yards of the shore. The depth gauge showed only 36 ft of water. If Japanese patrol boats appeared, the submarine would have perhaps 90 seconds to crash dive. Even then, she might hit bottom before fully submerging.

Flucky was betting everything on surprise and darkness. The eight men assembled on deck wearing dark clothing. Saunders checked his watch. Midnight was approaching. Flucky gave the order. The rafts went over the side. The rafts hit the water at 05 on July 23rd. Saunders and Walker took the lead raft with Hatfield and Sever.

The second raft carried Nuland, Clingalsmith, Richard, and Marcus. The men pushed off from Barb’s hull and began paddling toward the invisible shoreline. No lights, no sound except the dip of paddles and the whisper of water against rubber. The cloud cover held. Darkness remained absolute. Behind them, USS Barb sat low in the water, a darker shadow against the black ocean.

25 minutes to reach the beach. The men paddled steadily, maintaining formation. The surf was light, no breakers to contend with. The rafts grounded on sand at O30. All eight men dragged the boats above the high tide line and secured them behind rocks and driftwood. Nuland and Richard stayed with the rafts as guards. Their job was to ensure the escape route remained open and to signal Barb if Japanese patrols approached.

The other six men moved inland. They were the first American combat troops to set foot on one of Japan’s four main home islands. Karafuto was part of the Japanese prefecture system administered from Tokyo, populated by Japanese civilians and defended by Japanese military forces. Every step they took was on enemy sovereign territory.

Getting caught meant execution. The Geneva Convention didn’t protect saboturs operating behind enemy lines in civilian clothes. The terrain was rougher than expected. High grass concealed uneven ground. Sever nearly twisted his ankle in a depression hidden by vegetation. They moved slowly, testing each step before committing their weight.

50 yards inland, they encountered a drainage ditch 3 ft deep, water at the bottom. The men lowered themselves into the ditch, crossed the muddy bottom, and climbed the opposite bank. Their clothing was now wet and heavy. 100 yards from the beach, they reached a packed earth road, vehicle tracks visible in the dirt. The road ran parallel to the railroad connecting coastal villages.

Saunders signaled a halt. The men crouched in the grass beside the road and listened. No engine sounds, no voices, no movement. They crossed quickly, one at a time, then continued toward the railroad embankment, visible as a dark ridge against the slightly lighter sky. At 050, they reached the base of the railroad embankment.

Walker and Saunders climbed to the tracks and examined the area. The rails ran north south on a raised bed of gravel and crushed rock. Wooden ties spaced evenly beneath the steel rails. The position offered good visibility in both directions. Too good. If a patrol came along the tracks, the shore party would be completely exposed.

They needed to work fast. But before they could begin digging, Sever grabbed Saunders’s arm and pointed north. A faint vibration in the rails. Then a distant sound. A train was coming. The men dropped flat in the grass beside the embankment. Hadfield pulled the pickle jar containing the explosive device tight against his chest.

The vibration grew stronger. The sound became a rhythmic chugging, a locomotive pulling freight cars through the darkness. The train appeared from the north at approximately 055. No headlight, complete blackout conditions. The locomotive passed within 15 ft of where the Americans lay hidden, steam hissing, wheels clacking over rail joints.

The men could feel the ground shaking. Freight cars followed. 1 2 5 10. The shore party counted silently. 15 freight cars. Then the train was passed, continuing south toward Kashiho. The sound faded into the distance. Saunders waited two full minutes after the train disappeared before giving the signal to move. The men climbed onto the embankment and took positions.

Clinging, Sever, and Walker spread out as centuries. Clinging moved north along the tracks 50 yards. Sever went south the same distance. Walker positioned himself where he could see both directions and watch the road they had crossed. That left Saunders, Hatfield, and Marcus to dig and plant the device. Hatfield selected the location.

A straight section of track where an approaching train would be traveling at maximum speed. No curves to slow it down. No grade to reduce momentum. The rails here ran level across flat ground for at least half a mile in both directions. Perfect.Hatfield knelt between the rails and examined the ties.

He needed to bury the explosive directly beneath the rail where the locomotive’s weight would depress it enough to trigger the micro switch. Saunders and Marcus began digging with the improvised tools. The gravel came away easily at first, but 6 in down they hit compacted earth mixed with larger rocks. The digging became harder, slower.

The steel shovel scraped against stones. Each sound seemed impossibly loud in the darkness. Hatfield kept checking his watch. They had been on shore for 30 minutes. Flucky would wait 90 minutes maximum before Barb had to dive. The clock was running. At 015, Sever whistled softly from his position south along the tracks. Another train was coming.

The shore party dropped flat again. This train was approaching from the south, moving north, the opposite direction from the first one. Hatfield lay beside the partially excavated hole, still clutching the pickle jar. The digging tools were scattered across the gravel between the rails. If the locomotive’s headlight was on, the engineer would see everything.

The mission would be compromised. Japanese troops would flood the area within minutes. But like the first train, this one ran in complete darkness. No headlight. The blackout protocols the Japanese were enforcing along the coastal railroad were protecting the American savurs. The locomotive thundered past at 0117. Another freight train.

14 cars this time. Hatfield counted them as they clattered overhead. The shore party remained motionless until the sound faded completely to the north. Two trains in 22 minutes. The railroad was more active at night than Fluckyy’s observations had suggested. Saunders motioned the men back to work. They had less than an hour before Barb would need to submerge.

Marcus attacked the hole with renewed urgency. The shovel bit into the compacted earth. Rocks scraped free. Saunders used the pick to break up the harder sections. Within 15 minutes, they had excavated a space roughly 12 in square and 8 in deep directly beneath the western rail, large enough to accommodate the scuttling charge, the batteries, and the micro switch assembly.

Hatfield removed the components from the pickle jar. The 55lb scuttling charge was a cylindrical metal canister packed with high explosive. Enough power to blow a 3-FFT hole in a submarine’s pressure hull. Against the locomotive traveling at 40 mph, the effect would be catastrophic. Hatfield positioned the charge at the bottom of the hole and packed dirt around it to hold it steady.

Then he carefully placed the three dry cell batteries beside the charge and began wiring the circuit. The micro switch was the critical component. Hatfield had designed it to close when the rail above it depressed under the locomotive’s weight. Japanese locomotives typically weighed between 60 and 80 tons. That weight distributed across the wheels would push the rail downward approximately 1/4 to 1/2 in.

The micro switch needed to be positioned precisely. Too deep and the rail wouldn’t depress enough to trigger it. too shallow and vibrations from normal track expansion might cause a premature detonation. Hatfield worked by touch more than sight. His waterproof flashlight provided minimal illumination directed downward into the hole to prevent the beam from being visible at a distance.

He connected the positive terminal from the batteries to one side of the micro switch. The negative terminal ran to the scuttling charge detonator. The final connection from the detonator back to the micro switch would complete the circuit. But Hatfield left that wire disconnected. He would make the final connection last just before they departed.

Until then, the device was safe. At 0135, Hatfield had the wiring completed except for the final connection. He looked at Saunders and nodded. Saunders signaled Walker. The centuries began pulling back to the work site. Clingellesmith returned from the north, sever from the south. Walker came up from his observation position near the road.

The six men gathered at the tracks. Hatfield made the final connection. The circuit was now live. Any significant downward pressure on the rail above the micro switch would trigger the explosion. He covered the device carefully with dirt and gravel, smoothing it to match the surrounding ballast. No visible disturbance.

A track inspector walking this section in daylight might notice the slightly disturbed gravel, but a locomotive engineer traveling at speed in darkness would see nothing unusual. The shore party moved off the railroad embankment and began working their way back toward the beach.

Same route in reverse, across the road, through the drainage ditch, through the high grass. They moved faster now. The mission was complete. The explosive was armed. Every minute they remained on Japanese soil increased the risk of discovery. At 0145 they reached the beach where Nuland and Richard were waiting with the rafts.

Alleight men dragged the raft to the water line and climbed aboard. Saunders checked the luminous dial on his watch. They had been ashore for exactly 1 hour and 40 minutes. Barb would be preparing to dive. The rafts pushed off from the beach and the men began paddling toward the position where the submarine waited. The distance back to Barb was 950 yd.

In calm water with experienced paddlers, that meant roughly 15 minutes. They were halfway to the submarine when Fluffy’s voice cut through the darkness. He was shouting through a megaphone from Barb’s conning tower, telling them to paddle faster. Another train was coming down the tracks. The men in the rafts could hear it now, the distant sound of a locomotive building speed.

Flucky had spotted the train through Barb’s periscope while tracking the shore party’s return. The headlight was off, but the locomotive’s exhaust plume was visible against the mountain silhouette. The train was approaching from the north, heading directly toward the section of track where Hatfield had buried the explosive device.

The timing was going to be catastrophically close. Saunders and his men drove their paddles into the water with desperate rhythm. The rafts were still 400 yd from Barb. The submarine sat impossibly low in the water, her hull barely visible even at close range. Flucky had moved her to within 600 yd of the shore, decreasing the distance the rafts needed to travel, but putting Barb in water so shallow she would scrape bottom if she attempted a crash dive.

Every man aboard the submarine who wasn’t essential to operations was on deck watching the shore and the approaching train. The rafts closed the distance. 300 yd 200. The sound of the train grew louder. Through the darkness, the men paddling could now see the locomotive silhouette. It was traveling fast, probably 40 or 45 mph.

The engineer was making up time, pushing hard through the coastal section where the tracks ran straight and level. The locomotive was perhaps a mile north of the buried explosive, maybe 90 seconds away. Flucky had a decision to make. If he waited for the rafts to reach bar before diving, the submarine might be caught on the surface when Japanese response forces arrived after the explosion.

Coastal artillery could open fire. patrol boats could converge on their position. But if he submerged now, the eight men in the rafts would be stranded on the surface with no way to escape. Flucky made his choice. He ordered Barb to turn and prepare for emergency dive, but he would wait. The shore party had earned that much. The rafts reached Barb at 0146.

The men scrambled up the submarine’s hull and through the deck hatches. Saunders was the last man off the rafts. The rubber boats were cut loose and abandoned. They would drift and eventually sink. No time to retrieve them. Fluky ordered the deck crew below and sealed the hatches. Barb’s diesel engines rumbled to life.

The submarine began turning away from shore, accelerating toward deeper water. At 0147 on July 23rd, 1945, the northbound train reached the section of track where the micro switch waited. The locomotive’s lead wheels passed over the device. 68 tons of steel and steam pressing down on the rails. The western rail depressed. The micro switch closed.

The electrical circuit completed. 55 lbs of high explosive detonated directly beneath the locomotive’s boiler. The explosion was visible from barb. Even though the submarine was now 700 yd offshore and accelerating, a massive fireball erupted along the railroad embankment. The locomotive’s boiler ruptured instantly, adding superheated steam to the explosion.

Metal fragments shot upward in a fountain of burning debris. Pieces of the engine flew 200 f feet into the air, tumbling end over end before crashing back to Earth. The locomotive itself disintegrated. The boiler split into three sections. The drive wheels separated from the chassis. The smoke stack and cab section were hurled forward, cartwheeling down the embankment toward the beach.

The freight cars following the locomotive had no time to break. The first car slammed into the wreckage at full speed and accordioned. The second car climbed up and over the first, its wooden frame splintering. The third car jack knifed sideways and rolled off the embankment. Cars 4 through 16 piled into the growing mass of twisted metal and shattered wood.

The sound reached Barb as a rolling thunder that echoed off the coastal mountains. Fires ignited across the wreckage. Ammunition in several cars began cooking off, adding secondary explosions to the chaos. Flucky ordered all non-essential personnel topside to witness what they had accomplished. Dozens of submariners crowded onto Barb’s deck and conning tower.

They watched the fires burning along the Karafuto coastline. Japanese propaganda would later claim the train was carrying civilian passengers. American intelligence indicated otherwise. trains running at night on coastal militaryrailroads were transporting troops and war material. The men aboard that train were soldiers headed south to reinforce defensive positions against the expected American invasion.

Soldier uniform replicas

Barb continued accelerating toward deeper water. Within 10 minutes, the submarine would be in water deep enough to dive safely. Flucky allowed himself a moment to consider what his crew had just achieved. They had destroyed a Japanese military train using a submarine. The first and only time in naval history such an operation had been executed successfully.

But more importantly, they had conducted the only Allied ground combat operation on Japanese home island soil during the entire Pacific War. The celebration was premature. Japanese search lights were sweeping the water from coastal positions, looking for the submarine that had just declared war on their railroad. The search lights originated from at least three different coastal positions.

Japanese military installations responding to the explosion. The beam swept across the water in coordinated patterns, searching for the submarine they knew must be responsible. Barb was still on the surface, running at maximum speed toward deeper water. Her dark gray paint helped her blend into the black ocean, but if one of those search light beams caught her, coastal artillery would open fire within seconds.

Fluki ordered a course change, angling northeast away from the search pattern. Barb’s diesel engines were running at 150% overload, the same emergency power setting Fluki had used during the escape from Namcoan Harbor. The submarine was making 23 knots on the surface, leaving a phosphorescent wake that would be visible if the search lights got close enough. The depth gauge showed 48 ft.

Still too shallow for a safe dive, but better than the 36 ft they had been operating in near shore. At 0200, Barb crossed into water 60 ft deep. Fluky gave the order to dive. The submarine’s bow tilted downward as ballast tanks flooded. The deck crew had already secured all topside equipment. Within 90 seconds, Barb was completely submerged and leveling off at periscope depth.

The search lights continued sweeping the surface above them, but the submarine was invisible now. Fluki maintained slow speed on electric motors to minimize noise signature. Japanese patrol boats would be launching soon if they hadn’t already. The submarine stayed submerged for 6 hours, moving slowly away from Kafudo while Japanese forces searched the coastal waters.

At 0800 on July 23rd, Fluki risked raising the periscope. No patrol boats visible. The search lights had been extinguished with dawn. Smoke still rose from the railroad embankment where the train had exploded. Barb surfaced in deeper water and resumed patrol. But the mission wasn’t complete. Flucky had 4 days remaining before Barb needed to return to Midway.

He intended to use every hour. Over the next 72 hours, Barb continued attacking Japanese coastal targets. On July 24th, the submarine surfaced off Cherry and used her 4-in deck gun to shell a military radio station. Direct hits destroyed the antenna array and set the building on fire. On July 25th, Barb attacked a small shipyard at Shirakco, destroying two wooden coastal freighers under construction.

On July 26th, the submarine fired her final 12 rockets at a military garrison on Kaio Island, then withdrew toward open ocean. Japanese aircraft had been searching for Barb throughout the final patrol days. Reconnaissance planes crisscrossed the Sea of Otsk, trying to locate the submarine that was terrorizing their coastal infrastructure.

Flucky evaded them through constant movement and by diving whenever aircraft were spotted. On July 27th, Barb set course for Midway Island. The 12th and final war patrol was complete. USS Barb arrived at Midway on August 2nd, 1945. The crew assembled on deck in dress uniforms holding the submarine’s battle flag.

The flag was unlike any other in the United States Navy. 17 patches representing ship sunk. Symbols for the presidential unit citation and Navy unit commenation. Rocket and gun symbols denoting shore bombardments. Six Navy crosses earned by crew members. 23 silver stars. 23 bronze stars. a Medal of Honor ribbon at the top representing Flies award from the previous patrol.

And at the bottom center of the flag, a new symbol, a Japanese locomotive, the only submarine in history to sink a train now displayed that achievement on her battle colors. Admiral Chester Nimttz himself came to Midway to greet Barb’s crew. The flag was photographed for Naval Archives.

Eight men posed with the flag, the same eight who had gone ashore on Kafuto and planted the explosive that destroyed the train. Saunders, Hatfield, Sever, Nuland, Clinglesmith, Richard, Marcus, and Walker. They looked like ordinary sailors, young men who might have been working in factories or on farms if not for the war.

But they had accomplished something no military force had managed during the entire Pacific conflict. Theyhad conducted offensive ground operations on Japanese home island territory. The train explosion became legendary within the submarine service. Other boats had attacked shore targets with deck guns. Some had launched rockets like Barb, but no other submarine had put men on enemy soil to destroy a target and extracted them successfully.

The mission represented a new capability. Submarines weren’t just commerce raiders or torpedo platforms. They could project power ashore through sabotage and special operations. Flucky received his fourth Navy Cross for Barb’s 12th patrol. The citation specifically mentioned the train attack and the rocket bombardments. Combined with his Medal of Honor and three previous Navy crosses, Flucky became one of the most decorated submarine commanders in American naval history.

But when reporters asked him about his achievements, he consistently deflected credit to his crew. 6 days after Barb reached Midway, the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. 9 days later, Japan surrendered. The war ended before USS Barb could conduct another patrol. Japan’s surrender on August 15th meant the submarine’s combat career was over.

12 war patrols spanning three years. Five in the Atlantic theater during the early war years, seven in the Pacific, where Barb had compiled one of the most devastating records of any submarine in the American fleet. The official tally credited her with sinking 17 enemy vessels totaling 96,628 tons, but those numbers didn’t capture the full scope of what Barb had accomplished.

The Joint Army Navy Assessment Committee reviewed Fly’s claims after the war. They confirmed the destruction of the escort carrier Uno on September 17th, 1944, 22,500 tons. The carrier had been transporting aircraft and pilots from Japan to the Philippines when Barb’s torpedoes found her in the South China Sea. The ship sank in 40 minutes, taking most of her crew and cargo to the bottom.

Barb had also destroyed numerous smaller warships, frigots, patrol craft, coastal defense vessels. The attacks on merchant shipping had strangled supply lines feeding Japanese garrisons across the Pacific. But the train remained Barb’s most famous kill. Naval historians would spend decades analyzing the mission, the planning, the execution, the risks.

What made the operation remarkable wasn’t just its audacity, it was the proof of concept. Submarines could conduct operations far beyond traditional anti-shipping warfare. They could launch missiles. They could bombard shore installations. They could insert sabotage teams onto hostile territory and extract them successfully.

The mission on Kafuto demonstrated capabilities that would define submarine warfare for the next 70 years. Flies innovation with the rocket launcher proved particularly preient. In 1945, submarines launching rockets at shore targets seemed like a desperate improvisation born from lack of merchant shipping to attack.

But within a decade, submarines armed with guided missiles became the most powerful weapons platforms in naval arsenals. The Regulus Cruise Missile Program, Polaris Ballistic Missiles, Trident, Ohioass submarines carrying enough nuclear firepower to destroy entire nations. All of them traced their conceptual lineage back to Flucky bolting a Mark 51 rocket launcher onto Barb’s deck and proving the concept worked.

USS Barb herself had a less glorious post-war fate. The submarine was decommissioned in May 1947 and placed in reserve. recommissioned in 1951 for training duties. Decommissioned again in February 1954. That same year, she underwent Guppy conversion, a modernization program that gave World War II submarines improved underwater performance.

In December 1954, Barb was loan to the Italian Navy under the Mutual Defense Assistance Act. The Italians renamed her Enrio Tazulli after an Italian submarine commander from World War I. The submarine served in the Italian Navy for 18 years. By 1972, she was obsolete, worn out, no longer economically viable to maintain. The Italian government sold Enrico Tazulli for scrap metal.

The final price was approximately $100,000, roughly the cost of a modest house. When Flucky learned what had happened, he reportedly said that if the crew had known, they would have pulled their money to buy Barb and bring her back to the United States as a museum ship. But by the time anyone realized, the submarine was already being cut apart in an Italian scrapyard.

Only Barb’s battle flag survived. The Submarine Force Library and Museum in Grten, Connecticut, acquired it for their collection. Visitors can see it today displayed behind glass. The 17 ship symbols, the train at the bottom, the Medal of Honor ribbon at the top. The flag tells the story more eloquently than any historical account.

Eugene Flucky remained in the Navy after the war. He served as an aid to Secretary of the Navy James Foresttoall, then to Admiral Chester Nimttz. In 1960, President Eisenhower approved his promotion to Rear Admiral. Fluckycommanded the amphibious Group 4, served as president of the Naval Board of Inspection and Survey, commanded the entire Pacific Submarine Force from 1964 to ’66, and finished his career as director of naval intelligence.

He retired in 1972 after 37 years of service. Retirement didn’t mean inactivity. Flucky and his wife Marjgerie moved to Portugal and opened an orphanage in 1974. They ran it for eight years, providing homes for children who had lost families. Marjgery died in 1979. Flucky remarried in 1980 and continued the orphanage work until it closed in 1982.

In 1992, he published Thunder Below, his memoir of commanding USS Barb. The book became required reading at the Naval Academy. Flucky died on June 28th, 2007. He was 93 years old. He was buried at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis. But there was one statistic Flucky valued more than all the tonnage sunk, all the medals earned, all the recognition received. Zero.

Zero Purple Hearts awarded to anyone who served under his command during five war patrols. Zero casualties. That statistic defined Eugene Flucky’s command philosophy more than any tactical innovation or daring raid. He took calculated risks, but never reckless ones. He pushed his crew to the absolute limits of submarine capability, but never beyond the point where training and skill could compensate for danger.

Five war patrols, hundreds of depth charge attacks, thousands of miles through minefields and shallow water. Countless hours surfaced in enemy controlled seas, and every single man who served under Flucky came home alive. The crew members of USS Barb went on to live ordinary post-war lives. Saunders returned to civilian work.

Hatfield went back to the railroad industry. The others married, raised families, worked regular jobs. They rarely spoke about what they had done on Kafudo. The mission remained classified for years. Even after declassification, the men didn’t seek publicity. They had been doing their jobs, following orders, trying to end the war and get home.

The fact that their job involved paddling ashore on enemy territory to blow up a train was simply what the situation required. But history remembers what they accomplished. The eight men who went ashore that night in July 1945 conducted the only Allied ground combat operation on Japanese home islands during the entire Pacific War.

No Marines landed on Honu. No army troops fought on Hokkaido. No paratroopers dropped on Kyushu. The only American combatants to engage enemy forces on Japanese sovereign home island territory were eight submariners from USS Barb, armed with shovels, a pickle jar full of batteries, and 55 lbs of high explosive.

The mission’s impact extended beyond the immediate destruction. The train explosion forced Japanese military planners to divert resources to coastal railroad defense. Guards were increased. Patrols were expanded. Engineering units were assigned to inspect tracks daily. Those resources came from somewhere else.

Troops who might have reinforced defensive positions, equipment that might have been used against American invasion forces. The psychological effect was equally significant. If American submarines could strike inland targets with impunity, nowhere was safe. The rocket attacks Flucky pioneered had similar effects. Coastal factories and military installations were no longer protected by distance from the ocean.

A submarine could surface 3 mi offshore and destroy targets that previously required air raids. The 72 rockets Barb fired during her 12th patrol demonstrated a capability that would revolutionize naval warfare within a generation. The numbers tell part of the story. 17 ships sunk, 96,000 tons of enemy shipping destroyed, four Navy crosses and a Medal of Honor for the commander, eight battle stars for the submarine, the first rocket attack from a submarine, the first and only submarine to sink a train. But the most

important number was zero. Zero casualties among the crew during five combat patrols. Flucky brought every man home. That was his greatest achievement. Not the tonnage, not the metals, not the tactical innovations that changed submarine warfare forever. He brought his men home alive. USS Barb’s battle flag hangs in a museum in Connecticut.

The locomotive symbol at the bottom still draws questions from visitors who don’t know the story. When they learn what happened on July 23rd, 1945, they understand. They understand that submarine warfare wasn’t just about torpedoes and periscopes. It was about innovation, adaptation, courage, and commanders who valued their crews lives above personal glory.

Eugene Flucky, Paul Saunders, Billy Hatfield, and the 72 other men who served aboard USS Barb during those five patrols proved what submarines could accomplish when led by brilliant commanders and crewed by sailors willing to paddle ashore on enemy territory with explosives and shovels. They sank ships. They fired the first submarine launched missiles. Theydestroyed coastal targets.

And they blew up a train. The only submarine in history that can make that claim. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day.

stories about submariners who changed naval warfare with rockets and courage. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world.

You’re not just a viewer, you’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here.