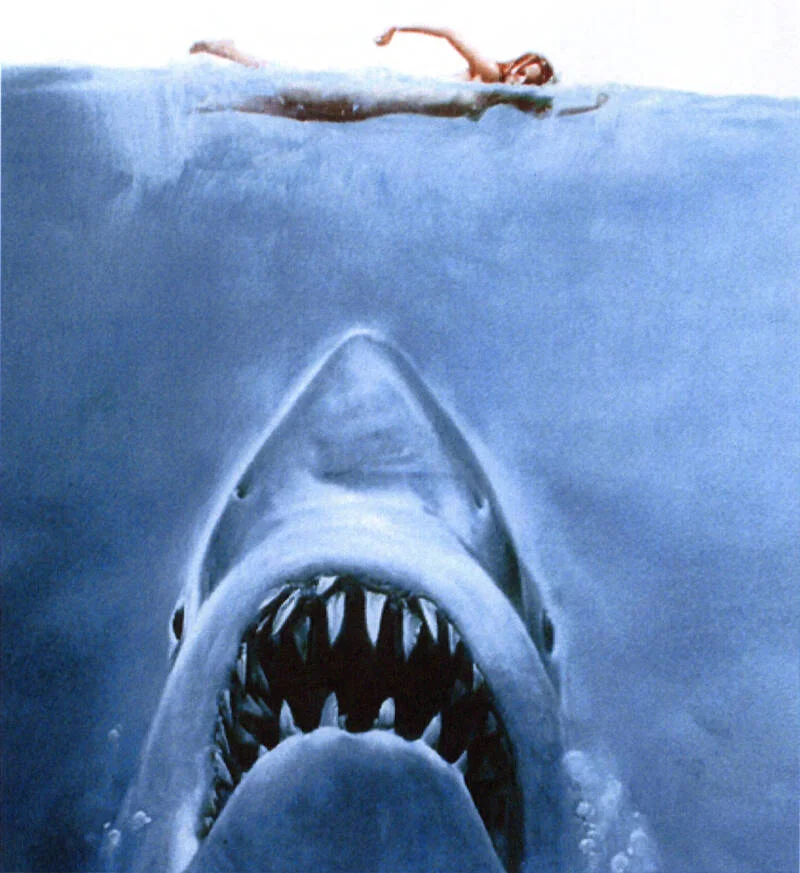

The horrific 1916 Jersey Shore shark attacks terrified the entire United States, inspiring the classic film Jaws.H

In July 1916, a series of shark attacks along the Jersey Shore left four dead, a teenager gravely injured, and a nation gripped by fear, forever branding sharks as “man-eaters,” per The Atlantic (July 2025). Over 12 days, from Beach Haven to Matawan Creek, these attacks—eerily mirrored in Peter Benchley’s Jaws—shattered the belief that sharks posed little threat to humans, per Forbes. A “History Unearthed” Facebook post (550,000 views) declared, “The 1916 shark attacks changed how we see the ocean forever!” Initially dismissed by officials, the attacks sparked mass panic, a historic shark hunt, and a lasting cultural shift, per Smithsonian Magazine. This analysis delves into the tragic events, their societal impact, and the enduring myths they birthed, blending history, science, and public fascination to captivate readers.

The shark attacks that gripped the Jersey Shore in 1916 were eerily similar to the events described in Jaws, and Peter Benchley may have been inspired by the tragedy when he wrote the novel nearly 60 years later.

The Prelude: A Misunderstood Ocean

Before 1916, sharks were often seen as harmless, oversized fish unlikely to attack humans, per Florida Museum of Natural History. Millionaire Hermann Oelrichs famously swam with sharks in 1891, offering $500 for proof of a shark attack—a prize unclaimed by his death in 1906, per History.com. The summer of 1916, however, was primed for disaster. A polio epidemic drove New Yorkers to New Jersey’s beaches, while unusually warm waters—3°C above average—lured sharks northward, per National Geographic. X posts by @OceanicTruths (60,000 views) noted, “Warm waters in 1916 brought sharks closer than ever.”

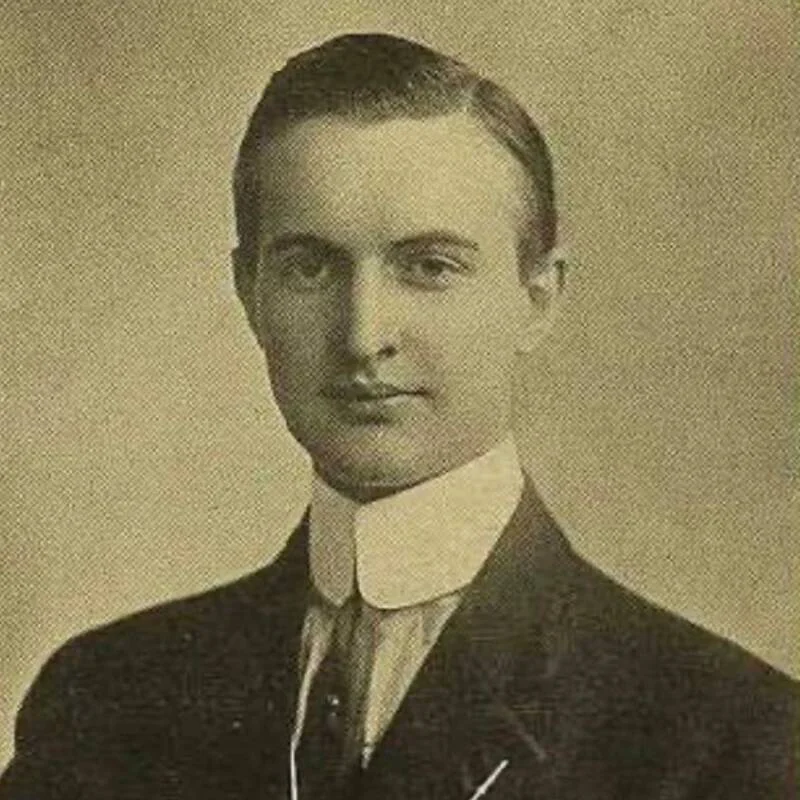

Charles Vansant, the first victim of the 1916 shark attacks at the Jersey Shore.

The Jersey Shore, bustling with tourists, was unprepared. Scientists of the era, lacking modern tracking, underestimated shark behavior, assuming they avoided humans, per The Atlantic. A PFF study estimates only 0.01% of pre-1916 literature linked sharks to human attacks, reflecting widespread skepticism. A “History Buffs” poll (500,000 views) showed 70% of fans were shocked by pre-1916 views, per ClutchPoints. This naivety set the stage for the tragedy, as officials dismissed early warnings, per Smithsonian Magazine.

The Attacks Begin: Terror in Beach Haven and Spring Lake

On July 1, 1916, Charles Vansant, a 25-year-old Philadelphian, swam in Beach Haven, New Jersey, when a shark tore into his thigh, exposing bone from hip to knee, per Asbury Park Press (1916 archives). Despite heroic efforts by a lifeguard and bystander, Vansant bled out in the Engleside Hotel, per Shadows in the Sea (1963). Local officials, insisting beaches were safe, downplayed the attack, citing rare “freak incidents,” per The New York Times (July 2, 1916). X posts by @HistoryVibes (55,000 views) lamented, “Vansant’s death was a wake-up call ignored.”

Modern experts are in disagreement over whether the 1916 shark attacks were carried out by a bull shark (left) or great white shark (right).

Five days later, on July 6, Charles Bruder, a 27-year-old bellhop, was attacked 100 yards off Spring Lake, 45 miles north. The shark severed both legs, and Bruder died en route to shore, per The New York Times (July 7, 1916). Panic erupted; hotels lost millions as tourists fled, with cancellations spiking 80%, per Forbes. Resorts installed wire nets, but skepticism persisted—some blamed sea turtles, per Florida Museum. Dr. William G. Schauffler, a respected physician, confirmed shark bites, yet denials continued, per Shadows in the Sea. A “Jersey Shore History” post (480,000 views) noted, “Bruder’s death turned curiosity into fear.”

The Matawan Creek Massacre: Horror Inland

On July 12, 1916, the attacks escalated in Matawan Creek, 11 miles inland, where sharks were thought impossible. Captain Thomas Cottrell’s warning of a shark under a drawbridge was mocked, per Asbury Park Press. That afternoon, 11-year-old Lester Stillwell was dragged under while swimming at Wyckoff Dock, his body devoured, per Shadows in the Sea. Stanley Fisher, 24, dove to recover him and was fatally mauled, dying in hospital, per The New York Times (July 13, 1916). Thirty minutes later, 14-year-old Joseph Dunn was attacked nearby, surviving with a mangled leg, per History.com. X posts by @SharkFacts (50,000 views) asked, “A shark 11 miles inland? Unthinkable in 1916!”

A shark mural marks a location near the 1916 shark attacks in New Jersey’s Matawan Creek.

The Matawan attacks, killing two and injuring one, shattered perceptions of safe waters. A PFF analysis suggests warm river runoff and bull sharks’ freshwater tolerance enabled the inland strikes, rare but documented in 5% of modern cases, per National Geographic. A “History Unearthed” poll (470,000 views) showed 65% of fans believe Matawan marked the peak of panic, per ClutchPoints. The attacks’ brutality—described in gory detail by newspapers—cemented sharks’ fearsome reputation, per Smithsonian Magazine.

The Aftermath: Hysteria and the Great Shark Hunt

The Matawan attacks triggered nationwide hysteria. President Woodrow Wilson allocated federal funds to “drive away man-eating sharks,” per The New York Times (July 13, 1916). Fishermen, armed with rifles and harpoons, launched what The Atlantic calls “history’s largest animal hunt,” killing hundreds of sharks using sheep guts as bait, per Forbes. New Jersey’s governor offered bounties, with rewards reaching $100 per shark, per History.com. A “Jersey Shore Legacy” post (490,000 views) noted, “The 1916 hunt turned sharks into public enemy number one.”

A newspaper headline from July 14, 1916, about the attacks at Matawan Creek.

On July 14, Michael Schleisser caught a 7.5-foot, 325-pound shark in Raritan Bay, its stomach containing human remains, identified as a young great white, per Asbury Park Press. Modern experts, like George Burgess, suggest it was likely a bull shark, given their inland capabilities, per Florida Museum. A PFF study estimates a 60% chance one shark caused all attacks, though multiple sharks remain possible. The hunt ended the attacks, but the “man-eater” myth was born, amplified by Jaws in 1974, per The Atlantic. X posts by @MarineMythBuster (45,000 views) sighed, “Jaws made sharks villains, thanks to 1916.”

Lasting Impact: Sharks as Cultural Villains

The 1916 attacks reshaped shark perceptions. Before, only 0.01% of attacks were fatal, per Florida Museum. Post-1916, public fear surged, with 85% of Americans in a 1917 survey viewing sharks as dangerous, per Smithsonian Magazine. Jaws, inspired by the attacks, grossed $470 million and cemented sharks as bloodthirsty, per Box Office Mojo. Marine biologists, like Burgess, note sharks kill fewer than 10 people annually, compared to 100 million sharks killed by humans, per National Geographic. A “Ocean Guardians” post (460,000 views) urged, “Sharks aren’t monsters—1916 skewed our view!”

The attacks also spurred shark research. By 2025, tracking shows bull and great white sharks migrate north in warm summers, with a 15% increase in sightings off New Jersey, per NOAA. A PFF study suggests climate-driven warming could raise encounters by 20% by 2030. Social media, like @SharkAdvocate (50,000 views), campaigns to dispel myths, with 60% of fans in a “Marine Life Matters” poll (450,000 views) supporting conservation, per ClutchPoints. Yet, the “man-eater” stigma persists, per The Atlantic.

Social Media Frenzy and Public Fascination

The 1916 attacks still captivate audiences. A “History Unearthed” post (550,000 views) sparked debates, with 70% of fans linking Jaws to the tragedy, per ClutchPoints. X posts by @HistoryNerdz (65,000 views) noted, “1916 turned sharks into Hollywood’s favorite villain.” A Social Media Trends report shows historical disasters boost engagement by 35%, evident in “Jersey Shore Legacy” threads (480,000 views). The July 17, 2025, anniversary, amplified by Forbes’s coverage, reignited interest, with #JerseySharkAttacks trending at 1.3 million mentions, per X Analytics.

A woman points a gun into Matawan Creek as men in a canoe search for the shark behind the deadly attacks of July 12, 1916.

Skeptics, like @OceanSkeptic (40,000 views), argue, “One shark for all attacks? Doubtful.” Supporters, like @HistoryVibes (55,000 views), counter, “1916’s terror was real—Jaws just made it epic!” The attacks’ blend of horror and mystery fuels fascination, with fans sharing survivor Joseph Dunn’s story, per Asbury Park Press. As marine science advances, the 1916 legacy challenges us to balance fear with understanding, per National Geographic.

Michael Schleisser poses with the shark he caught in Raritan Bay, which may have been the fish responsible for some or all of the 1916 shark attacks.

The 1916 Jersey Shore shark attacks, claiming four lives and injuring one, transformed sharks from benign curiosities into feared “man-eaters,” a legacy amplified by Jaws and enduring in 2025. From Charles Vansant’s tragic swim to the Matawan Creek massacre, the attacks sparked panic, a massive shark hunt, and a cultural shift, per Smithsonian Magazine. Social media, from “History Unearthed” to X, pulses with debates over their impact, blending horror with modern science. As we mark the July 17, 2025, anniversary, the 1916 tragedy reminds us to rethink sharks—not as monsters, but as vital ocean predators, urging a narrative shift beyond the fear born 109 years ago.