No One Thought He’d Last 10 Minutes — Then This Man Fought for 2 Hours and Saved His Entire Regiment. H

No One Thought He’d Last 10 Minutes — Then This Man Fought for 2 Hours and Saved His Entire Regiment

Early morning, February 1st, 1944, near Sistna, Italy. Private First Class Alton W. Nappenburgger lay alone at top a small exposed null. From positions 85 to 120 yd away, three German MG42 machine guns were firing simultaneously. Before his eyes, his entire platoon was being torn to pieces.

Bullets skimmed low, kicking up dirt. The Browning automatic rifle in his hands weighed 11 kg fully loaded, and his magazine held only 20 rounds. A crack was embedded in the wooden stock. A 7.92 mm bullet that should have pierced his skull had instead grazed the wood. According to the infantry field manual, at this moment, he should have sought cover, kept a low profile, and retreated immediately. But Nappenburgger did not.

Discover more

Biographical documentaries

Artillery fire simulation

Detective novels

Instead, he crawled to the most conspicuous, deadliest position on the entire battlefield and held his ground there, unmoving for a full 90 minutes. By 200 p.m. that afternoon, this 20-year-old deer hunter from Spring Mount, Pennsylvania, who had never before had a confirmed kill, had inflicted at least 60 German casualties, shattering a counterattack that could have completely flattened the American beach head.

The tactic he used was simple to the point of brutality. If you want to understand how a country deer hunter used the mindset of ambushing bucks in the Pennsylvania woods to kill 60 trained German soldiers, you must first see clearly what he saw that morning. The entire battlefield. Alton Warren Nappenburgger was born on December 31st, 1923 in Spring Mount, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

Medal of honor

It was a rural area. His father worked in a factory and his mother managed the household. Alton grew up hunting for sport, tracking white-tailed deer in the woods around Spring Mount from the age of 12. His most proficient hunting technique was the high ambush, setting up a treeand or ground blind at a position higher than the deer trail.

This concealed a simple tactical logic. Height determines field of view. Deer move on the ground and rarely look up. The hunter lies in weight, overlooking the entire hunting ground, controlling every move of the prey. Patience is the core of this technique. Sitting motionless for 6 hours, never acting rashly, one shot to hit, taking only one deer. Ammunition was expensive.

The cartridges for his father’s Winchester30 rifle cost good money and could not be wasted. The hunter must wait for the perfect moment. aim and then pull the trigger. Reading the terrain was a fundamental skill. Before climbing the treeand, Alton would survey the entire forest.

Discover more

the king. Elvis

Military strategy guides

Uncategorized news feed

Where would the herd pass? Which paths did they frequent? Where were the feeding grounds? The position of the treeand had to be chosen at the optimal point to monitor all prey movements. The hunter always controlled the initiative of the hunt. Before the war, Alton worked at a brick factory in Spring Mount, carrying 50 lb bricks for 10 hours a day.

This hard labor forged his strong muscles and amazing endurance. But what truly allowed him to escape death in the Battle of Anzio was the instinct honed during his hunting life. In March 1943, 16 months after Pearl Harbor, Alton was drafted into the army under the Selective Training and Service Act. He did not enlist voluntarily.

The army sent him to Fort me, Maryland for basic training where he first encountered the M1 Garand rifle fed by an 8 round clip semi-automatic weighing 4.3 kg. Shortly after he was assigned as a Browning automatic rifleman, this M1,918. A two Browning automatic rifle, BAR for short, was a squad automatic weapon.

Fully loaded, it weighed 11 kg, more than double the Garand with a magazine capacity of 20 rounds, far exceeding the Garand’s 8. The BAR had two fire rate modes, slow 300, 450 rounds per minute, and fast 500 650 rounds per minute, firing the same 30 06 Springfield cartridge as the Garand. Although the BAR was heavier and slower to reload, it provided suppressive fire the Garand could not match.

The infantry field manual repeatedly emphasized. Use cover. Keep a low profile. Conserve ammunition. Alton took these rules to heart, but hunting had taught him another set of survival laws. Seize the high ground. Expand your field of view. Control the battlefield. In September 1943, the US Third Infantry Division known as the Rock of the Mann set out for the Italian theater.

Alton was assigned to Company C, 30th Infantry Regiment, participating in Operation Avalanche and landing at Solerno. Over the next 4 months, they fought across the Volterno River, advanced step by step toward Monte Casino, and reached Anzio after a bloody campaign. Alton always performed his duties faithfully, charging with the BR, firing on command, keeping his head down at all times.

His comrades gave him the nickname nappy. He was unremarkable, had never received any medals or commendations, and had never been singled out by superiors for bravery. He was just an ordinary rifleman in a rifle company. On January 22nd, 1944, Operation Shingle began. Allied forces landed at Anzio in Natuno, 50 km south of Rome, aiming to outflank the German Gustaf line and open the road to Rome.

The landing achieved surprise, catching the Germans offguard, but the American commander, Major General John P. Lucas, hesitated. He did not order an immediate advance on Rome, choosing instead to consolidate the beach head. This fatal hesitation gave German field marshal Albert Kessler time to mobilize troops.

Within a mere 48 hours, elite German units had surrounded the beach head, including the battleh hardardened Herman Guring Panzer Division and the Third Ponzer Grenadier Division. By January 30th, the Allies had been compressed into a narrow strip 15 km deep and 25 km wide, and the Germans immediately launched a counterattack, attempting to drive the Allies back into the sea.

From January 30th to 31, the Battle of Cesterna broke out. US Ranger units attempted to break through the German lines and seize the strategic town of Cesterna De Latina 15 km inland but suffered a disastrous defeat. Darby’s Rangers were encircled by the Germans with 761 killed or captured. The third infantry division tried its best but could not break through the encirclement to affect a rescue.

By February 1st, the Germans were preparing a massive counterattack, planning to split the Allied beach head in two and destroy the pockets one by one. On the night of January 31st, Company C received orders. Before the expected counterattack began, send a patrol to scout German positions near Cesterna. Alton prepared six magazines for his BR, totaling 120 rounds.

At 11:30 a.m. on February 1st, 1944, the patrol moved out. Company C moved in a dispersed formation across the open farmland near Sernna with 30 to 40 soldiers advancing slowly. The land was flat and open. In the harvested wheat fields, only 10 to 15 cm of stubble remained. There were no trees, almost no cover, only a few shallow depressions in the ground.

The deepest no more than 30 cm. It was February in central Italy. The ground was semifrozen and the temperature was about 5° C. The patrol’s mission was simple and clear. Advance 300 m, identify the German positions, and then retreat. Alton walked on the right flank of the formation, gripping his bar, his hunter’s eyes scanning the wilderness vigilantly.

An ominous feeling welled up. This field was too empty. Where were the Germans? At 11:45 a.m., the first MG42 machine gun suddenly opened fire. The sound was highly distinctive, like a high-speed chainsaw cutting wood. Sharp and earpiercing with a fire rate of up to,200 rounds per minute. The German machine gun spat tongues of fire from a camouflaged position ahead.

The first burst instantly killed three American soldiers. The remaining members of the patrol scrambled to drop and seek cover, but the so-called cover was nothing more than shallow pits that barely concealed their bodies. Immediately after, a second MG42 on the left opened fire, followed by a third on the right joining the fry.

The patrol was caught in a perfect crossfire net, unable to advance or retreat, unable to move. Any slight movement would invite a hail of bullets. The second lieutenant shouted orders hoarsely, but no one could move a step. The three MG42s fired alternately, spraying for 5 to 7 seconds, pausing 3 to 4 seconds to change barrels or reload, then firing again.

Continuous suppressive fire left the Americans breathless. Within the first 15 minutes, another five soldiers were hit. One soldier tried to crawl toward the wounded, but MG42 bullets whistled in immediately. He could only scramble back. The patrol was completely paralyzed. From 11:45 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., a full 15 minutes of desperate stalemate ensued.

Alton lay in a shallow pit, BR muzzle pointing forward. He scrutinized the battlefield as if surveying a hunting ground. Although the MG42 positions could not be seen directly, they could not escape his eyes. The first machine gun nest was 85 yd ahead, muzzle flash and smoke betraying its location. The second was 100 yard to the left where he could see the trajectory of the barrel turning.

The third was 120 yard to the right, audible but invisible. All three nests were set in low-lying areas or behind sandbag bunkers, almost level with the ground. From a prone position, Alton could barely see them. But 60 yards in front of him, there was a small earthn null rising 2 to 3 meters above the surrounding fields.

It was the only high ground in this wilderness, offering a 360° view with no obstructions, but also no cover, completely exposed to German fire. Yet once at top that null, he would have the entire battlefield in view. A hunter’s thought of ambushing prey took shape in his mind. Standing on that null, I can see their positions.

They will see me, but I will see them more clearly. I will be the deer and let them become the hunters. As long as their guns are aimed at me, my comrades can be saved. Alton turned to the soldier beside him and said, “I’m going to that null.” The soldier’s eyes went wide and he shouted in disbelief, “You’re crazy.

You’ll be cut to ribbons in 10 seconds.” Alton replied, “If they’re staring at me, they can’t worry about the others.” “Nappy, don’t go.” But Alton had already started crawling forward. The lieutenant was 20 m away and didn’t notice his action at all. He didn’t ask for permission, didn’t wait for orders. He chose to improvise. At 12:05 p.m.

, Alton crawled toward the null 60 yd away. He dragged the 11 kg bar with his right hand, elbows propping up the ground, struggling forward through the wheat stubble. The semifrozen earth cut his palms. MG42 bullets whistled overhead. The Germans hadn’t spotted him yet, their attention entirely on the pinned down main body of the Americans.

Alton crawled past the body of an American soldier lying face down in the dirt, blood frozen. He didn’t pause for a moment. A burst of MG42 bullets swept past him, dirt splashing 2 m to his left. Alton froze instantly, motionless. After 10 seconds, the machine gun stopped. The Germans were reloading. He continued to crawl forward. 30 yard, 40 y, 50 y.

The Germans still hadn’t noticed. His movements were slow and concealed, keeping his profile low. The Germans attention was all on those bigger threats. Reaching the 50-yard mark, he arrived at the base of the null. The ground beneath his feet began to slope upward. Just a few final steps. Alton scrambled up the last 2 to 3 m of the slope using hands and feet, finally reaching the top of the null.

His position was now a cut above the surrounding fields. At this moment, if the Germans looked up, he was dead for sure. But the Germans didn’t. They were still firing madly at the trapped American platoon. Alton lay a top the null bar muzzle pointing forward. From this position, the entire open ground was fully visible and he saw all his targets clearly.

Machine gun nest number one 85 yd away. Three Germans, the MG42 mounted on a tripod with low sandbags for cover in front. Nest number two, 100 yd to the left. Two Germans clearly visible, one loading, one pulling the trigger. Nest number three, 120 yd to the right. Only the barrel exposed, the position extremely well camouflaged.

Behind him, 30 American soldiers were pinned down on a 150 m wide line, unable to move. Alton quickly made a tactical decision. Neutralize the nearest target first, nest number one at 85 yd. He switched the BR’s fire rate to slow mode, 300, 450 rounds per minute. In this mode, shooting was more accurate and ammo consumption lower.

At 12:10 p.m., Alton aimed at the gunner of nest number one, steadied his breathing, held his breath, and slowly pulled the trigger. The Bay fired four rounds in 1 second. Thud, thud, thud, thud. The German gunner fell backward in response. The loader turned to check the situation. Alton fired again, sending three bullets out.

The second German also slumped to the ground. The third German, terrified, turned and ran. MG42 number one was completely silenced. Germans in other positions heard the shots and immediately began searching for the source. 5 seconds later, they discovered Alton on the null. The remaining two machine gun nests immediately swiveled their barrels and bullets poured down like a rainstorm. The 7.

9 2mm bullets sliced through the air at supersonic speeds, screaming past him. Bullets hit the ground beside him, splashing dirt and sending gravel flying. One bullet grazed 6 in above his head. Another pierced his sleeve, tearing the fabric but missing the skin. A third bullet hit the bar’s wooden stock, chiseling a deep crack into it.

Alton quickly rolled 2 m to the right, changing his firing position. Movement is survival, a lesson learned while hunting. Deer can easily spot stationary objects. The German guns would aim at his previous location, not his current hiding place. Even moving just 1 or 2 meters was enough to change his fate.

At 12:12 p.m., two German grenaders approached from the left. They used leapfrog tactics, sprinting 5 to 10 m in a crouch, then dropping prone, then continuing. They were panzer grenaders, each carrying three to four stick grenades. Their goal clear, flank the null, get close, and throw grenades to kill Alton. The distance closed.

40 yard, 30 yd, 25 yd. Alton stared at the targets through his sights, but held his fire. The hunter’s patience was fully displayed at this moment. Wait for the best shooting opportunity. Never fire hastily. Let the prey get a little closer. 20 yards. The distance was just right. Alton fired a burst of six rounds.

The first grenadier was hit in the chest and fell instantly. The second grenadier hurriedly raised his hand, attempting to throw a grenade. Alton pulled the trigger again, firing four rounds. The second grenadier also fell. The grenade slipped from his hand and exploded 15 m away, its blast completely failing to reach the null. Two more Germans dead.

At 12:20 p.m., machine gun nest number two, 100 yards to the left, was still resisting stubbornly, the gunner sweeping the null continuously. Alton switched the bar to fast fire mode, 500, 650 rounds per minute. At a longer range, stronger suppressive fire was needed. Within 1.5 seconds, he fired 10 rounds.

Every fifth round was a tracer. The phosphorous tips dragged bright trails pointing straight at the German position. His goal was not to kill, but to suppress, forcing the German gunner to duck into cover. The sound of the MG42 ceased temporarily as expected. The Germans shrank behind the sandbags. Alton immediately fired a second burst, eight rounds whistling out. He saw a German fall backward.

The MG42 tried to fire again, but the crew was already in chaos with only one man barely operating it. Alton fired a third burst, sending six rounds out. MG 42 number two fell completely silent. Of the three machine gun nests, two had been eliminated. By this point, the German casualties caused by Alton were estimated at 8 to 10 men.

At 12:25 p.m., Alton checked his magazine. Only three rounds remained. There were two magazines left on his belt, totaling 40 rounds. His total ammunition on hand was only 43 rounds. Yet, nest number three on the right was still firing, and there were an unknown number of German infantry supporting on the flank.

Ammo was running out, and the BR’s barrel was scorching hot. In just 15 minutes, he had fired about 150 to 200 rounds. Unlike the water cooled M1,917 heavy machine gun, continuous firing of the BR could easily lead to an overheated and ruined barrel. His hands trembled slightly, not from fear, but from the adrenaline rush and the muscle strain of controlling an 11 kg weapon.

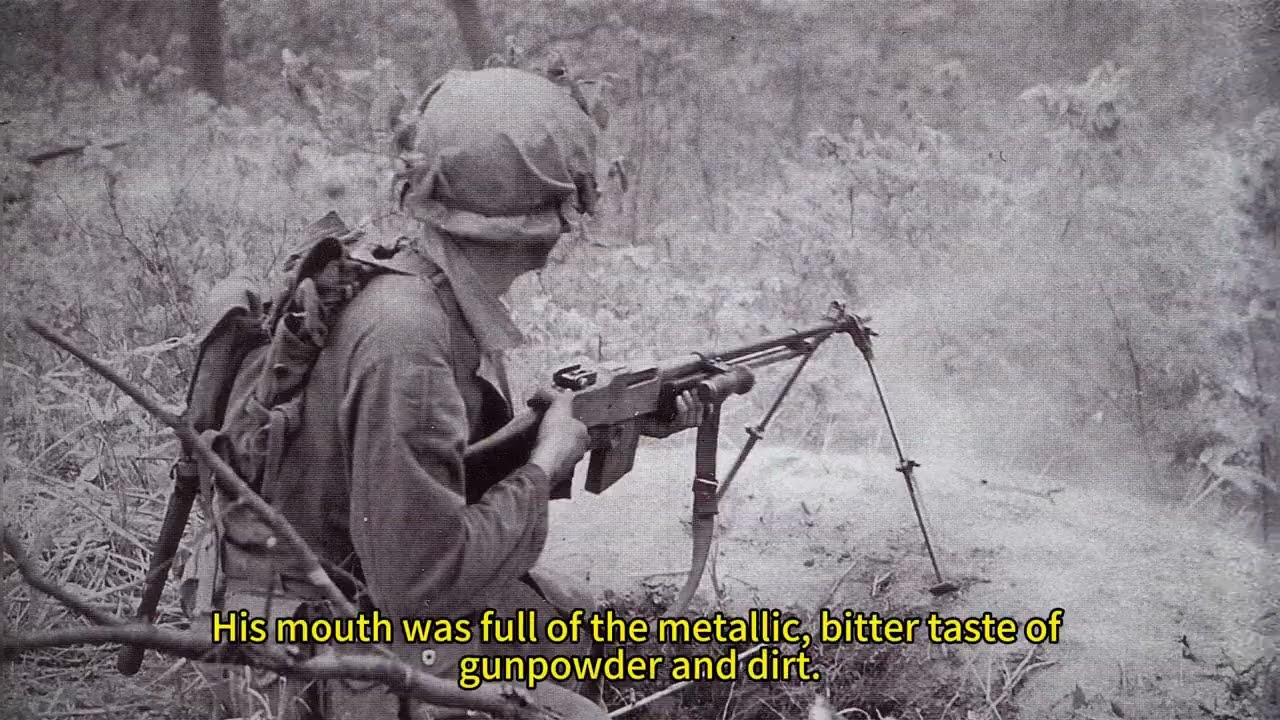

The bar’s recoil made his shoulder ache. His lips were cracked and peeling, and his canteen was left in the pack at the rear. He hadn’t had time to bring it when he set out. Alton spat to moisten his lips. His mouth was full of the metallic, bitter taste of gunpowder and dirt. At 12:30 p.m., a new threat appeared.

Alton saw 20 to 30 German soldiers surging from the rear. This was a German assault platoon aiming to take the null. They advanced in a staggered formation using leapfrog tactics. Half the men charged 10 to 15 m, stopped to provide cover fire while the other half followed up. Standard infantry tactics, methodical and orderly.

The distance shortened constantly. 150 yard. 120 yd. 100 yard. Alton made a snap decision. Ignore machine gun nest. Number three. At 120 yard, the bar would struggle to pose an effective threat to a fortified position. Priority: neutralize the infantry. They were closer and a more urgent threat. At 100 yd, Alton opened fire. Rate of fire set to fast mode.

He used short bursts to conserve ammo. Four rounds. Shift aim. Another four rounds. Shift again. Aiming exclusively at exposed targets, never wasting bullets on shots without certainty. German soldiers fell in groups. The first soldier took a hit to the chest and fell straight to the ground. The second was hit in the leg, screaming and curling into a ball. The third, fourth, fifth.

In just 30 seconds, five to six Germans were down. The remaining Germans hurriedly sought cover, either jumping into shell craters or hiding behind the bodies of their comrades. At 80 yards, Alton continued firing. Any German head that popped up invited a three to four round burst. A German just raised his head to observe.

A burst came and he fell. Another tried to crawl forward, unable to escape death. Another four to five Germans killed. Facing dense fire from the high ground, this assault platoon could not move an inch. A German officer shouted orders loudly, identified later as German, ordering a temporary retreat. The assault platoon withdrew in disarray.

In this engagement, German casualties were estimated at 10 to 12 men. Alton remained on the null unscathed. At 12:40 p.m., Alton pulled the trigger. Click. The magazine was empty. He quickly swapped in his last magazine. Only 20 rounds left. This was everything he had. To the right, 120 yd away, machine gun nest number three was still firing.

Bullets constantly landing around the null. One bullet struck 6 in to his left. the shockwave making his eardrums ring. A scene later written into his official Medal of Honor citation. Another bullet hit the barstock, sending wood chips flying. Yet another cut his sleeve, still without drawing blood. With only 20 rounds left, Nest number three was still resisting, and the Germans could launch a new charge at any moment.

I need more ammo now. Alton’s gaze fell 15 yards down the null, exactly where the dead American soldier he had crawled past earlier lay. The man had an M1 Grand rifle and a bandelier of ammunition on him. He faced a choice. Crawl down the null, exposing himself to German fire to snatch ammo, or stay put and run out of bullets when the Germans charged.

Rather than sit and wait for death, better to take a risk. At 12:43 p.m., Alton began crawling toward the body. The German MG42 gunner immediately spotted his movement. Bullets swept in like rain, dirt exploding beside him. Halfway there, a German grenade exploded 5 m to his right, the shock wave slamming dirt into his face. But he didn’t flinch.

The 15yd distance felt like the boundary between life and death. He finally reached the body, flipped it over, and felt for BR magazines. None found. This soldier used an M1 Garand carrying eight round clips, not the BA’s 20 round magazines. Fortunately, both used the same 3006 rifle cartridge.

He had to manually load the bullets from the Grand Clips one by one into the empty BR magazine, all under German fire. Alton unhooked the bandelier from the body. It held six grand clips, 48 rounds in total. The MG42 fire grew denser, bullets punching small holes in the ground around him. His hands shook violently from the adrenaline spike.

He grabbed the first clip, dumped the eight rounds into his palm, picked up an empty BR magazine, and began loading one by one. One round, two rounds, three rounds, eight rounds. He grabbed the second clip and continued. Nine rounds. 16 rounds. His hands were shaking too badly. He simply couldn’t fill it to 20. 16 rounds would have to do.

Alton cursed, stuffed the remaining clips into his pocket. About 32 rounds left, dragged the magazine loaded with 16 rounds, and crawled desperately back to the top of the null. At 12:46 p.m., Alton returned to the null. 16 rounds in the mag, 32 loose rounds in his pocket, total 48 rounds. He had the strength to fight again. From 1:00 p.m.

to 2 p.m., the battlefield fell into a brutal seesaw battle. The Germans launched flanking maneuvers time and again. Alton repelled them time and again with precise bursts. Every 15 to 20 minutes, the Germans would launch an attack. Yet, they could never get within a step of the null. At 1:20 p.m., machine gun nest number three on the right finally went silent.

The German crew either fled in panic or were all killed. The war records are not explicit. During this time, Alton reloaded his BR magazine from Garand clips three more times. Each reload took two to 3 minutes, extremely dangerous, completely exposed to German fire, but he had no choice. Over 2 hours, the total number of bullets he fired was approximately 200 to 250.

He had long lost count of how many Germans he had killed. Only one thought remained in his mind. Survive. Hold the position. At 2 p.m. exactly, the American platoon trapped for over 2 hours was finally able to move. With all three MG42 nests silenced, the soldiers either advanced to consolidate positions or pulled back to evacuate the wounded.

An officer, likely that second lieutenant, shouted toward the null, “Nappy, come down!” Alton fired his last few rounds, then crawled down the null and walked toward the American lines. His uniform had three bullet holes. The bar stock was full of cracks, and the barrel was still scorching hot. His comrades looked at him in total silence. Someone murmured.

He held off 2 hours of them all by himself. Alton said nothing, exhaustion washing over him like a tide. A medic came up to check his injuries and the result was unbelievable. He was unscathed without even a scratch. Was it a miracle? Was it luck? Or did his ceaseless movement save him? No one could give an answer.

A few days later, intelligence officers returned to the battlefield near the null to count German bodies. In front of the null lay about 20 to 25 German corpses. Around the machine gun nests and along the attack routes, there were about 35 to 40 bodies, plus signs of many German wounded having been evacuated.

It was confirmed that Alton had caused approximately 60 German casualties, including those killed in action and the seriously wounded who were evacuated. These casualties were distributed almost entirely within a 180° fan-shaped area in front of the null. Three dead at nestnum 1, two to four dead at Nestnum 2, two grenaders dead on the spot, 10 to 12 casualties in the assault platoon, and 20 to 30 casualties from other scattered skirmishes.

Major General Lucian Truscott, commander of the Third Infantry Division, called Alton Nappenburgger a one-man army, and the report recommending him for the Medal of Honor was rushed up the chain of command. From February to May 1944, after the Battle of Anzio ended, Alton continued to fight with the army.

The Third Infantry Division struggled to break the siege of the Beach Head. On May 23rd, Operation Diadem began and Allied forces successfully broke through the line. On June 4th, Rome was liberated and Alton entered the city with the Third Infantry Division. On May 26th, 1944, the Medal of Honor was officially awarded to Alton.

The official citation read, “He held an exposed null position. Enemy bullets whistled within inches. Under suppressive fire, he crawled 15 yards to secure rifle clips from a fallen comrade. Alone, he held off enemy attacks for over two hours, successfully shattering the enemy’s counterattack attempt.

At this time, Alton was only 20 years old and had experienced 5 months of baptism by fire. This was the first and only time in his military career that he received a commendation. After the award ceremony, Alton was sent back to the United States to participate in a war bond tour, recounting his combat experiences to call on the public to buy war bonds.

This was standard procedure for Medal of Honor recipients at the time. Did the US Army Infantry Field Manual change? Officially, no. The field manual still taught soldiers, use cover, keep a low profile. But the infantry school at Fort Benning listed Alton Nappenburgger’s deeds as a case study. How to adapt to local conditions.

Turn disadvantages into advantages. Trade exposure for field of view where field of view is battlefield control. When the command system is paralyzed, take the initiative to control the situation. This case conveyed a core idea. The manual is a guide, not an iron law. Terrain and battlefield situation always override the book.

Although Alton’s decision violated the manual, it was a stroke of genius for that open terrain. From 1945 to 2008, after the war ended, Alton returned to Pennsylvania. He first worked as a truck driver, then became a supervisor for an asphalt paving crew. He always stayed out of the public eye and rarely mentioned the war.

He married, had children and grandchildren, and passed on the skills he learned in hunting, fishing, and shooting to his children and grandchildren. His character was quiet and humble. A phrase he often said was, “I just did what I had to do.” Local veterans all knew him and knew he was a Medal of Honor recipient, but Alton never boasted of his achievements.

Unless someone asked actively, he never mentioned the past. On June 9th, 2008, Alton Warren Nappenburgger passed away at the age of 84. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. The gravestone is simple and plain, engraved only with his name, rank, PFC, and the words Medal of Honor. No mention of the 60 Germans.

No mention of the two hours on that null. In that open field near Cesterna de Latina, an inconspicuous null still stands today. No more than 2 to 3 meters high, completely unremarkable. On February 1st, 1944, this null was the most dangerous place within 10 square km. 20-year-old Alton Warren Nappenburgger, the deer hunter from Spring Mount, Pennsylvania, climbed this null. He lay in wait, waited, and fired.

Just like climbing a treeand to hunt, he survived and saved 30 immobilized comrades. His logic was simple and pure. I will be the deer and let them become the hunters. The infantry field manual said, “Seek cover.” Alton Nappenburgger said, “Seize the high ground. Look out over the battlefield.

Control the whole picture.” If Alton Nappenburgger’s story moved you, please like and support to let more people know about this forgotten history. Subscribe and turn on notifications. We push unknown historical stories daily. You are welcome to leave a message in the comment section, telling us where you are from and sharing if your family had relatives who participated in Wu 2.

Thank you for watching. Alton Nappenburgger deserves to be remembered. These men gave everything for the freedom of future generations. And by watching, liking and sharing, you are keeping their memory alive. Less we forget.