South Vietnam, March 23rd, 1967. Sergeant Ron Dasher Davies pressed his body against the wet earth, barely breathing. 15 meters ahead, a Vietkong patrol of eight men moved down the trail, their AK-47s slung casually over their shoulders, talking in low voices. They had no idea they’d walked within spitting distance of four Australian SAS troopers who’d been lying in that exact position for the past 11 hours.

Military history books

What happened next would seem impossible. As the VC patrol passed, Davies and his team didn’t move, didn’t fire, didn’t even shift their weight. They simply waited. [snorts] 5 minutes after the enemy disappeared down the trail, the Australians began their withdrawal. Moving in reverse, they retraced their route step by step, placing their feet in the exact same impressions they’d made coming in.

30 minutes later, they were 400 m away. The VC patrol would return down that same trail 6 hours later, searching for whoever had been watching them. They’d find nothing. No bootprints, no broken branches, no disturbed vegetation, no sign that anyone had been there at all. The Australians had vanished like smoke in wind.

And they’d done it using a technique so simple, so counterintuitive that it took the Americans 3 years to fully understand it. But here’s what made this technique revolutionary. While American units were crashing through the jungle like freight trains, leaving trails a blind man could follow, the SAS had mastered the art of moving through hostile territory and disappearing without a trace. And it wasn’t magic.

It was science, psychology, and obsessive attention to detail that most soldiers couldn’t comprehend. Before we show you exactly how they did it, make sure you hit that subscribe button and turn on notifications. This channel brings you the untold stories of elite combat operations. And we’ve got more incredible SAS tactics coming your way.

Vietnamese language course

Now, let’s dive into the secret that made the Australian SAS the most feared unit in Vietnam. The technique had a name, though few outside the SAS knew it. Tactical backtracking with pattern disruption. But that clinical description missed the reality. What the Australians had perfected was something far more profound.

Discover more

Special forces training

Special forces gear

Special forces documentaries

Military history books

Outdoor survival equipment

Jungle survival course

Military history tours

Military tactics guides

Stealth techniques seminar

Military intelligence services

the ability to move through an environment and leave it exactly as they found it, as if they’d never existed at all. The foundation of this ability wasn’t taught in a classroom. It was forged in the brutal terrain of northern Queensland during SAS selection, where candidates spent weeks learning something that seemed absurd to conventional soldiers.

Jungle survival kit

How to walk backwards through jungle without looking behind them. We’d spend entire days moving in reverse, recalled Corporal Jim Spider, who went through selection in 1965. The instructors would have us patrol forward for 2 km, then reverse our route. Exactly. If you left signs that weren’t there on the way in, you failed.

Discover more

First aid kits

Map reading course

Camouflage gear

Tactical backpacks

Invisibility technology research

Military intelligence services

science

Australian military history

Tactical footwear

Science

If you couldn’t find your own tracks to follow back, you failed. Most guys couldn’t handle it. They’d get disoriented, frustrated, and wash out. The psychological challenge was immense. Human beings are hardwired to move forward. Walking backwards through dense jungle where every step could be onto a snake, into a wait a while vine, or over a hidden drop required rewiring your entire cognitive approach to movement.

But the Australians understood something the Americans didn’t. In jungle warfare, your insertion route was your biggest vulnerability. Every broken branch, every disturbed leaf, every bootprint in mud was a signpost telling the enemy exactly where you were, where you’d come from, and potentially where you were going.

The technique they developed solved this problem with elegant simplicity. When withdrawing from an observation position or after an ambush, SAS patrols would move backwards, literally walking in reverse, stepping into their own footprints. This achieved three critical objectives. It eliminated new tracks that pointed toward their extraction point.

SAS recruitment info

It obscured the direction of their withdrawal. And most importantly, it created the illusion they’d vanished into thin air. The VC were expert trackers, explained Sergeant Major Harry Bronco Williams, who served three tours with the SAS in Vietnam. They could tell how many men were in a patrol, how much weight they were carrying, how long ago they’d passed, all from reading bootprints and bent grass.

But our technique broke their tracking model completely. They’d follow our insertion tracks to an observation position, find the position, but then the tracks just stopped. It was like we’d been lifted out by invisible helicopters. The physical execution was brutally difficult. walking backwards while carrying 40 pounds of equipment, maintaining 360 degree security, coordinating with three or four other team members doing the same thing, all while moving silently through terrain you couldn’t see behind you.

It required trust, training, and a level of spatial awareness that bordered on supernatural. The training progression started simple. In Queensland’s Jungle Training Center, candidates would spend their first week learning to walk backwards on marked trails during daylight. then unmarked trails, then at night, then through water, then up and down slopes.

Military history books

By week three, they were conducting full patrol exercises where the only movement allowed was backwards. “The first time you step backwards off a 2 m drop you didn’t know was there, you learn real quick to develop your senses,” Webb recalled with a grim laugh. “We learned to feel the terrain with our feet before committing weight.

We learned to sense obstacles through changes in air pressure and sound. It sounds crazy, but after a few weeks, you could move backwards through thick jungle almost as fast as moving forward. The technique evolved beyond simple backtracking. The Australians developed a sophisticated system they called pattern disruption that combined multiple elements to create complete invisibility.

First was the concept of false insertion. When helicopters dropped SAS patrols, they’d often touch down in three or four different locations, but only one would actually deploy troops. The others were dummy insertions designed to confuse enemy trackers. Then from the actual insertion point, the patrol would move 200 to 300 m in one direction, creating an obvious trail before backtracking to the insertion point and moving out in their real direction of travel.

Any VC trackers would follow the false trail, find where it ended, and assume the patrol had been extracted. Meanwhile, the actual patrol was kilome away, moving on their actual mission. Second was track mixing. Instead of moving in single file, which created an obvious patrol trail, the Sass would sometimes move in a staggered line where each man walked a slightly different route.

Jungle survival kit

This created multiple faint tracks instead of one obvious path, making it harder for trackers to determine how many men were in the patrol or which direction they were actually moving. Third, and most sophisticated, was environmental restoration. This went beyond simply walking in your own footprints. It meant actively restoring the environment to its pre- patrol condition.

If you had to cut a vine to pass through, you’d carefully position the cut vine to look naturally broken. If you disturbed a spiderweb, you’d use a twig to recreate web-like patterns. If you turned over a rock, you’d replace it with the same side up. If you bent grass, you’d gently work it back to its original position. We’d spend 20 minutes camouflaging a position we’d only occupied for an hour, explained trooper Dave Mouse Morris.

Americans thought we were crazy, wasting time when we should be moving to safety. But that time investment meant the VC never found our positions. They’d patrol right past places we’d spent days observing from and never know we’d been there. The Americans couldn’t believe it when they first saw it demonstrated.

In November 1966, Captain Mike Walsh, a US Army intelligence officer, was embedded with an SAS patrol specifically to document their techniques for possible adoption by American forces. Walsh watched Sergeant Bob Payton’s fourman patrol insert into a hot area of Fuok Tui Province. They moved 800 meters through dense jungle to an observation position overlooking a suspected VC supply route.

Military strategy books

For 36 hours, they lay motionless, observing enemy movement, taking photographs, and calling in coordinates for later strikes. When the time came to extract, Walsh expected the standard procedure. Move quickly to a secure landing zone. Get out fast. Instead, Patton’s team began their withdrawal by moving backwards, step by careful step, into their own tracks.

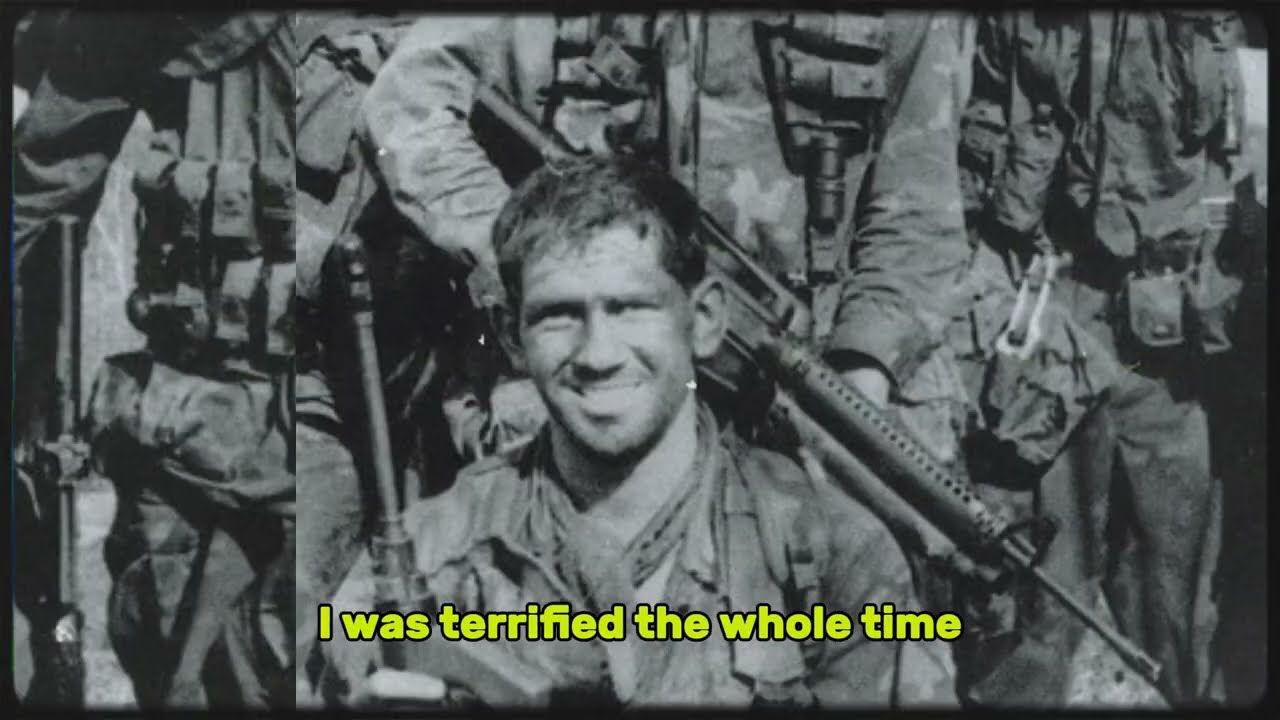

It took them 2 hours to move 800 m, Walsh wrote in his report. I was terrified the whole time. Every instinct screamed to move forward, move fast, get to safety. But they moved backwards with absolute discipline. When we reached the site extraction point, Patton had me walk back down our withdrawal route. I couldn’t find a single sign we’d been there.

The VC swept that area the next day. They found nothing. Walsh’s report concluded with a stark assessment. This technique is extraordinarily effective, but requires a level of training, discipline, and psychological fortitude that I doubt most American units could achieve. It is fundamentally counter to our military culture of aggressive forward movement. He was right.

Despite multiple attempts to train American units in tactical backtracking, the adoption rate never exceeded 30% and even units that tried it rarely achieved the same level of proficiency as the SAS. The reason was cultural and philosophical. American military doctrine emphasized speed and aggression, close with and destroy the enemy, maneuver warfare, fire superiority.

SAS recruitment info

The idea of spending hours carefully withdrawing backwards seemed cowardly, inefficient, wrong at a fundamental level. The Australians saw it differently. They’d learned in Malaya that survival in counterinsurgency warfare wasn’t about being the bravest or the most aggressive. It was about being the smartest and the most disciplined.

In an environment where the enemy could be anywhere, where you were always outnumbered, where calling for help meant waiting hours or days, your ability to appear and disappear without trace, wasn’t cowardice. It was the only thing that kept you alive. The technique saved lives in ways that were hard to quantify.

How do you count the ambushes that never happened because the enemy never found your trail? How do you measure the intelligence gathered from observation posts the enemy never discovered? How do you value the psychological impact of an enemy who couldn’t predict where you’d strike next? But there were quantifiable effects.

Wilderness tracking courses

SAS patrols using full pattern disruption techniques had a 93% chance of completing their mission without enemy contact. Patrols that couldn’t or didn’t use these techniques had only a 67% mission success rate. The difference between being invisible and being merely stealthy was the difference between ghosts and soldiers.

The VC response to SAS invisibility evolved throughout the war, revealing just how effective the technique was. By mid 1967, Vietkong units operating in Puaktui province had received specific instructions about the Maung jungle ghosts. A captured document from August 1967 included detailed guidance.

Enemy reconnaissance forces employ unusual movement techniques that make tracking difficult. Traditional tracking methods are insufficient. When signs of enemy presence suddenly stop, do not assume extraction. Establish wide security perimeter and search for 500 m in all directions. The VC were adapting, but their adaptation revealed their confusion.

Military strategy books

They’d fundamentally misunderstood what the SAS were doing. They thought the Australians were using some kind of advanced extraction technique, helicopters with special silent rotors, or perhaps being picked up by vehicles on hidden roads. They couldn’t conceive that men were simply walking backwards through the jungle because in their experience, no one could do that effectively.

Jungle survival kit

The VC themselves had tried similar techniques during their war against the French, but had abandoned them as too slow, too difficult, [clears throat] too impractical. We captured a VC tracker in September 1967 who’d been specifically trained to find SAS patrols, recalled Lieutenant Terry O’Neal, an intelligence specialist with the Australian Task Force.

He described spending 6 weeks learning to identify signs of backward movement, disturbed vegetation that had been repositioned, things like that. But he admitted they’d never successfully tracked an SAS patrol to an extraction point. He said it was like following a trail of smoke. The VC developed counter tactics specifically designed to defeat SAS invisibility.

They began placing trackers at suspected extraction points rather than trying to follow patrol routes. They started using tracker dogs, though the SAS quickly learned to defeat this by moving through water and using pepper and other scent masking agents. They even tried technological solutions, setting up networks of crude motion sensors made from bamboo and wire that would create subtle sounds when disturbed.

SAS recruitment info

But the SAS adaptation was always faster. They learned to spot these warning systems and either avoid them or move so carefully that they didn’t trigger them. The most sophisticated VC counter technique was psychological. They began spreading rumors among their own forces that the Australian commandos weren’t human, that they could teleport, that they were protected by spirits, that fighting them was cursed.

This wasn’t superstition for its own sake. It was calculated psychological warfare in reverse. By making their own soldiers believe the SAS had supernatural powers, VC commanders were trying to explain the inexplicable. How could enemy patrols disappear without trace? If the answer was supernatural rather than tactical, it preserved the VC fighters confidence in their own jungle craft and tracking abilities. But the strategy backfired.

Instead of maintaining morale, it created a deep-seated fear of operating in areas where the SAS were known to be active. Some VC units began refusing missions in Fuaktui province, specifically because of the Ma Rang. The technique’s effectiveness was proven in dozens of operations, but one stands out as the perfect demonstration of tactical invisibility.

Operation Canra, October 1967. A five-man SAS patrol under Sergeant Keith Payne was tasked with locating a VC regional headquarters believed to be operating somewhere in the Long Green Hills northeast of Newi dot. Previous American intelligence efforts had located the general area, but three battalionsized search and destroy operations had found nothing.

Jungle survival kit

Payne’s patrol inserted at dusk on October 12th using a false insertion technique. The helicopter touched down at four different locations in a 5 km radius. At two of them, the crew kicked out equipment bags to simulate patrol deployment. At one, they hovered for 30 seconds without landing. Only at the fourth did Payne’s team actually deploy.

From that insertion point, the patrol moved 300 m north, creating obvious tracks before backtracking and moving southwest toward their actual objective area. For the next 9 days, Payne’s patrol moved through an area where VC activity was constant. They observed enemy patrols, watched supply movements, and documented what appeared to be a significant command presence, but they never established a static observation post.

Instead, they used a technique called rolling surveillance. Each day, they’d move to a new observation position, spend 12 to 18 hours observing, then withdraw using their backtracking technique, and move to a new position. This meant the VC never found observation posts because the patrol never stayed in one place long enough to leave significant sign and every position they left was meticulously restored to appear undisturbed.

On day seven, the patrol identified what they’d been looking for. A concealed headquarters complex in a small valley, virtually invisible from the air, but bustling with activity at ground level. For the next 48 hours, they observed from multiple positions, photographing the complex, counting personnel and documenting routines.

Military strategy books

They identified what appeared to be a senior VC commander based on the difference other fighters showed him. The extraction came on October 21st. Instead of moving directly to an extraction point, Payne’s patrol moved in the opposite direction for 400 m, then backtracked and moved to their actual pickup zone. The entire withdrawal took 4 hours for a distance most patrols would have covered in 45 minutes.

The intelligence they provided enabled a coordinated strike 2 days later. Australian artillery and American air strikes destroyed the headquarters complex. The operation killed an estimated 47 VC, including the regional commander, and scattered the unit for months. But here’s the critical part. The VC never knew they’d been under observation.

When they rebuilt their headquarters 2 months later, they did it in almost the exact same location, assuming the strike had been based on signals, intelligence or informant information, not ground reconnaissance. That told us everything we needed to know about how well our technique worked. Payne later reflected, “They simply couldn’t conceive that we’d been sitting 200 m from their headquarters for 2 days watching them, then vanished without them knowing we’d been there.

Wilderness tracking courses

” The American attempts to replicate SAS invisibility techniques produced mixed results, revealing both the power of the method and its limitations. In early 1968, MACV established a specialized training program at Na Trang, where SAS instructors taught American long-range reconnaissance patrol units the fundamentals of tactical backtracking and pattern disruption.

The first course had 60 students from various LRRP units. By the end of the six-week program, 23 had completed the training to SAS standards. The rest couldn’t master the psychological and physical demands of backward movement through jungle terrain. It wasn’t that they weren’t good soldiers, explained Sergeant Jim Trog Truscott, one of the SAS instructors.

Most of them were excellent, but they’d been trained their whole careers to move forward aggressively. Asking them to spend hours carefully withdrawing backwards felt wrong to them at a gut level. You could see the frustration. [snorts] They understood intellectually why it worked, but they couldn’t make themselves do it when it counted.

The American units that did master the technique achieved remarkable results. [snorts] A LRP team from the 101st Airborne Division conducted a 14-day reconnaissance mission in the Asha Valley in April 1968 using full SAS pattern disruption techniques. They provided intelligence on NVA logistics that enabled a major operation and extracted without the enemy ever knowing they’d been there.

SAS recruitment info

But these successes remained exceptions. The institutional momentum of American military culture was too strong. Speed, aggression, and firepower remained the dominant tactical values. The patient, disciplined invisibility the SAS practiced never became mainstream in American forces. Some American special operations units adopted modified versions of the technique.

Navy Seal teams operating in the Meong Delta found that backtracking through water was particularly effective since bootprints in mud could be walked backwards through to eliminate obvious direction of travel. Army special forces reconnaissance teams learned to use false trails and environmental restoration even if they couldn’t master full tactical backtracking.

The results were positive, but never matched SAS effectiveness rates. The fundamental issue was time. SAS patrols would spend 4 hours withdrawing from a position that American doctrine said should take 45 minutes. In a military culture that valued operational tempo and maintaining pressure on the enemy, that time investment seemed wasteful.

But the SAS measure of success was different. They weren’t trying to maximize number of operations. They were trying to maximize intelligence gathered while minimizing casualties and ensuring the enemy never adapted to their patterns. We’d rather do one operation perfectly than three operations adequately, explained Major Ian Gordon, who commanded an SAS squadron in 196970.

Jungle survival kit

The Americans did more, but we did better. It’s a different philosophy. Neither is wrong, but they can’t be mixed. You either commit to invisibility or you don’t. The technique evolved throughout the war. By 1970, SAS patrols had refined their methods to include aerial deception, where they’d request helicopter flybys over false extraction points hours after they’d already walked out.

This created the illusion of helicopter extraction and further confused enemy tracking efforts. They developed layered backtracking where the patrol would move backwards for 200 m, then forward for 100 meters in a different direction, then backwards again. This created a track pattern so confusing that enemy trackers couldn’t determine actual direction of travel.

They even experimented with delayed restoration where they deliberately leave obvious sign at certain points knowing the enemy would find it and assume it was an operational security failure. This sign would lead to nothing, while the patrol’s actual route, perfectly camouflaged, would go undetected. If you’re finding these tactics as fascinating as we do, hit that like button and drop a comment telling us what other Vietnam war operations you want to hear about.

Military strategy books

We read every comment and use your suggestions for future videos. Now, let’s talk about the long-term impact of these techniques. The long-term impact of SAS invisibility techniques extended far beyond Vietnam. When the Australian SAS returned home in 1971, they brought with them refined doctrine that would influence special operations worldwide for decades.

The British SAS, already impressed with their Australian counterparts, fully incorporated tactical backtracking into their own training programs. These techniques would prove crucial in Northern Ireland, where moving through hostile territory without leaving trace was often the difference between successful intelligence gathering and deadly ambushes.

The technique influenced American special operations development in unexpected ways. When Colonel Charlie Beckwith created Delta Force in 1977, he specifically studied SAS operations in Vietnam. While Delta never fully adopted tactical backtracking, they incorporated the underlying philosophy. Invisibility is a force multiplier.

Modern special operations forces worldwide now teach variations of pattern disruption and environmental restoration. SEALs, special forces, Rangers, and their equivalents in other nations all learn that eliminating your trace isn’t just good fieldcraft. It’s strategic deception. The technique has evolved with technology.

Military history books

Modern special operations teams use GPS to mark their exact insertion routes, making backtracking more precise. Night vision devices make backward movement in darkness safer and faster. But the core principle remains the best way to defeat trackers is to appear to vanish. Interestingly, the technique has found applications beyond military operations.

Search and rescue teams use pattern disruption techniques to avoid disturbing evidence at disaster sites. Wildlife researchers use environmental restoration to minimize their impact on animal behavior. Even some archaeological expeditions employ these methods to preserve sight integrity. But perhaps the most profound impact was psychological and philosophical.

The sea proved that in warfare the most powerful move isn’t always the most aggressive one. Sometimes disappearing is more devastating than attacking. Sometimes being invisible is more valuable than being overwhelming. This lesson directly challenged the prevailing military doctrine of the 1960s and 70s which emphasized firepower, speed, and decisive action.

The SAS showed that patience, discipline, and invisibility could achieve strategic effects that conventional operations couldn’t match. The Vietkong never fully adapted to SAS invisibility techniques. Even by 1971, when the Australian task force withdrew from Vietnam, captured documents showed VC forces were still struggling to understand how SAS patrols could appear and disappear seemingly at will.

SAS recruitment info

A former VC commander interviewed in 1989 admitted, “We developed tactics for every enemy force. For the Americans, we learned to listen for helicopters and avoid their patrols. For the South [snorts] Vietnamese, we learned to infiltrate their ranks. For the Koreans, we learned to avoid their areas because they were too brutal.

But for the Australian commandos, we never developed a reliable counter. They were simply better at jungle warfare than we were. And that was difficult to accept. That admission from an enemy commander 14 years after the war ended reveals the true measure of SAS effectiveness. They’d achieved something rare in military history.

Tactical superiority so complete that the enemy never found a reliable counter. The techniques limitations must be acknowledged. Tactical backtracking required ideal conditions, dense vegetation for concealment, soft ground that held bootprints, sufficient time for careful withdrawal, and patrol members trained to an exceptional standard.

In open terrain, on hard ground or under time pressure, the technique was less effective or impossible. It also required small patrol sizes. Four to six men could coordinate backward movement effectively. Larger units created too many tracks and too much complexity. This meant the technique was inherently limited to reconnaissance in small-cale operations, not conventional infantry tactics.

Wilderness tracking courses

And it demanded extraordinary discipline. One patrol member breaking protocol leaving an obvious sign or failing to restore the environment could compromise the entire technique. This is why SAS selection had a 90% failure rate. They weren’t just looking for skilled soldiers. They were looking for men with the psychological makeup to maintain absolute discipline under extreme stress.

Modern countertracking technology has also reduced the techniques effectiveness. Thermal imaging, motion sensors, and drone surveillance can detect patrol movement in ways that traditional tracking cannot. While pattern disruption still has value, it’s no longer the definitive answer to invisibility it was in Vietnam.

But the core principles remain valid. Every modern special operations force emphasizes minimizing your signature, whether physical, electronic, or thermal. The SAS taught the world that the enemy can’t kill what they can’t find, and they can’t find what leaves no trace. The human cost of perfecting this technique is often overlooked.

During SAS training in Vietnam, several near misses occurred when patrol members stepping backwards encountered unexpected obstacles. A three meter drop, a snake, a pungy stake pit. The difference between near miss and casualty was often just luck. I stepped backwards into a hornet’s nest during a withdrawal in June 1968, recalled trooper Mark Ellison.

Military strategy books

Got stung 30 times, but couldn’t react. Couldn’t swat at them. couldn’t make noise because there was a VC patrol 40 m away. Just had to take it. Keep moving backwards. Maintain discipline. That’s what the technique demanded. Complete physical and psychological control under conditions most people can’t imagine. These stories, rarely told, reveal the human reality behind tactical innovation.

The SAS didn’t just develop clever techniques in comfortable training facilities. They perfected them under conditions of extreme discomfort, danger, and stress, where failure meant death. The technique also created unique psychological bonds between patrol members. When your survival depends on every team member maintaining perfect discipline during hours of backward movement through hostile jungle, trust becomes absolute.

You’d trust your patrol members with your life because you literally were trusting them with your life every single day, explained Corporal Dave Morris. If one guy broke discipline, made noise, left obvious sign, we all died. That creates a bond that’s hard to explain to people who haven’t lived it. This psychological dimension, the absolute trust and mutual dependence, was perhaps as important as the physical technique itself.

Vietnamese language course

It created cohesion that allowed four-man patrols to operate for weeks in enemy territory without external support, knowing that every member would maintain discipline no matter what happened. The techniques evolution continues today. Modern Australian SAS still teaches tactical backtracking, though now enhanced with technology.

GPS tracking allows patrols to follow their exact insertion route in reverse with centimeter precision. Night vision and thermal imaging make backward movement safer. Communications equipment allows real-time coordination between patrol members, but the fundamental challenge remains unchanged. Can you move through hostile territory and leave no trace of your passage? Can you become invisible not through technology but through discipline and technique? Can you vanish like smoke? The Australian SAS proved the answer was yes.

And in doing so, they wrote a chapter in military history that’s studied worldwide but rarely matched. Before we wrap up, remember to subscribe to this channel and hit that notification bell. We’re bringing you more untold stories of elite military operations every week. And you won’t want to miss what’s coming next.

Drop a comment below telling us what you think of these SAS tactics and which Vietnam war story you want to hear next. The legacy of SAS invisibility techniques lives on not just in military doctrine, but in a philosophical approach to special operations that prioritizes intelligence over action, patience over aggression, and invisibility over presence.

SAS recruitment info

In modern counterterrorism operations, special operations forces worldwide employ these principles. The most successful raids are often those the enemy never saw coming because the reconnaissance teams were never detected. The most valuable intelligence comes from observation posts the enemy never discovered. The SAS technique of tactical backtracking and pattern disruption proved that the human element, skill, discipline, psychological fortitude remains decisive even in an age of advanced technology. Satellites can see

everywhere, but they can’t track what leaves no trace. Sensors can detect movement, but they can’t find patrol routes that appear to end in thin air. When Sergeant Ron Davies and his patrol vanished from that trail in March 1967, they didn’t just evade one VC patrol. They demonstrated a principle that would echo through special operations for generations.

The most dangerous enemy isn’t the one you can see and fight. It’s the one you never knew was there. The Vietkong called them Maung, jungle ghosts. And perhaps that’s the most fitting name because ghosts don’t leave footprints. Ghosts don’t disturb branches or bend grass. Ghosts appear, complete their mission, and vanish as if they never existed.

Jungle survival kit

The Australian SAS didn’t use magic to disappear in the Vietnamese jungle. They used something more powerful, mastery of environment, discipline that bordered on superhuman, and a technique so simple yet so difficult that even today, few can replicate it. They walked backwards through hell, and hell never knew they were there.

That’s the trick the Australian SAS used to vanish in Vietnamese jungles. Not supernatural power, not advanced technology, just four men, absolute discipline, and the willingness to do what others thought impossible. If you made it this far, you’re the kind of viewer we love. Hit that like button, subscribe for more untold military stories, and we’ll see you in the next video. Stay tactical.